Be Fu**ing Perfect: (Booby) Traps along the Road of Perfection

By Chiara Pussetti (University of Lisbon)

The exhibition Be Fu**ing Perfect—through different lenses and languages, between anthropology and art—presented the results of the project EXCEL: The Pursuit of Excellence. Biotechnologies, Enhancement and Body Capital in Portugal,[i] which I have coordinated over the past four years at the Institute of Social Science at the University of Lisbon. The project is dedicated to the desires, imaginaries, and practices of human enhancement in Portugal. The title of the exhibition, Be Fu**ing Perfect, ironically alludes to the “pursuit of excellence and perfection” inherent in our contemporary liberal society, based on the imperative of self-surveillance to discipline the body through various forms of manipulation and self-responsibility through the acquisition of resources in the interest of personal success in a competitive regime.

The research I have conducted on enhancement practices in Portugal demonstrates that being deemed successful today is therefore not a matter of luck but of individual responsibility. In a neoliberal logic, it is expected that we are all responsible for our choices regarding the image we want to portray and about the consumer products we should or should not acquire. The body is a signifier of social status and capability, so good appearance is associated with opportunity and success in a society that greatly values beauty. These bodily disciplines take on a voluntary form: the normative standards that regulate and control bodies and subjectivities are experienced not as external obligations or rules but as personal aspirations and desires. The individual, far from being a “product” of the surrounding environment, is an autonomous entrepreneur of their own future.

The products and procedures offered by the “betterment” industry are increasingly prevalent, easily accessible, and less invasive in today’s society. With the fast progress of these technologies, the body, particularly the female one, has been always more actively subjected to continual production and alteration in order to be “perfected.”

But this investment is not for everyone. Large sectors of the population are excluded: those who do not have the financial resources to buy the perfect body are therefore discriminated against even more, reproducing already existing social hierarchies. Those who have the option select high-quality cosmetic products and aesthetic interventions. Those who cannot afford this luxury often resort to risky solutions—unsuitable products and dangerous practices without any kind of medical regulation or guaranteed result. In our research, we met people injecting industrial silicone, sealing glue, or liquid cement as materials for aesthetic modification of body contour. In our very unequal world, this means that a wide swath of humanity is largely excluded from these technologies of self-improvement, as the more desirable technologies become branded as luxury items, limited only to those with access to the best health-care systems or with the purchasing power to buy the ideal body.

Beauty matters. It constructs our identity and defines our self-perception, it shapes our social opportunities, it structures our daily practices, and it symbolizes and produces personal and collective meanings. Beauty matters because it is simultaneously a coveted ideal and a moral obligation, and we spend a lot of time and money to achieve it. Regardless of social class or economic status, appearance is important to us all—men, women, nonbinary, or genderqueer individuals (Jarrín and Pussetti 2021; Pussetti 2021; Pussetti, Brandão, and Rohden 2020; Pussetti, Rohden and Roca 2021). In the exhibition, however, we focused mainly on the cis female body. Although aesthetic concerns are also important for male subjects, there is a gendered difference in the time and financial resources that women invest in beauty work. The fantasy of perfect beauty and eternal youth, linked to a Euro-American neoliberal ideology of limitless enhancement and absolute autonomy of the individual, is firmly entrenched in moralizing definitions of gender norms. Women are under normative pressure to take responsibility for their bodies and to invest in their constant maintenance and improvement. They are encouraged to take control of their life and their body, to assume responsibility for the way they look, and to maintain their self-discipline on a daily basis.

Considering femininity as a site for endless transformation, change, and makeover, we dealt with women’s “aesthetic entrepreneurship,” focusing on “real” material bodies and appearance ideals and norms shaped by intersectional differences, such as social class, sexual orientation, race, or generation. Adopting an intersectional paradigm in the understanding of femininity as a process, the project examines notions of femininities and body ideals as plural and fluid without falling into the trap of just centering women’s bodies and only the social practices of cisgender women. What it means to be feminine in urban Portugal today has nothing to do with women’s bodies at all. Ongoing cultural changes—linked to rapid urbanization, globalization, technological change, and digital media—are in motion in Portuguese society, transformative of gender identities and performances. In fact, femininities cannot be understood separate from their intersections with other important facets of identity (i.e., race, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, culture, education, etc).

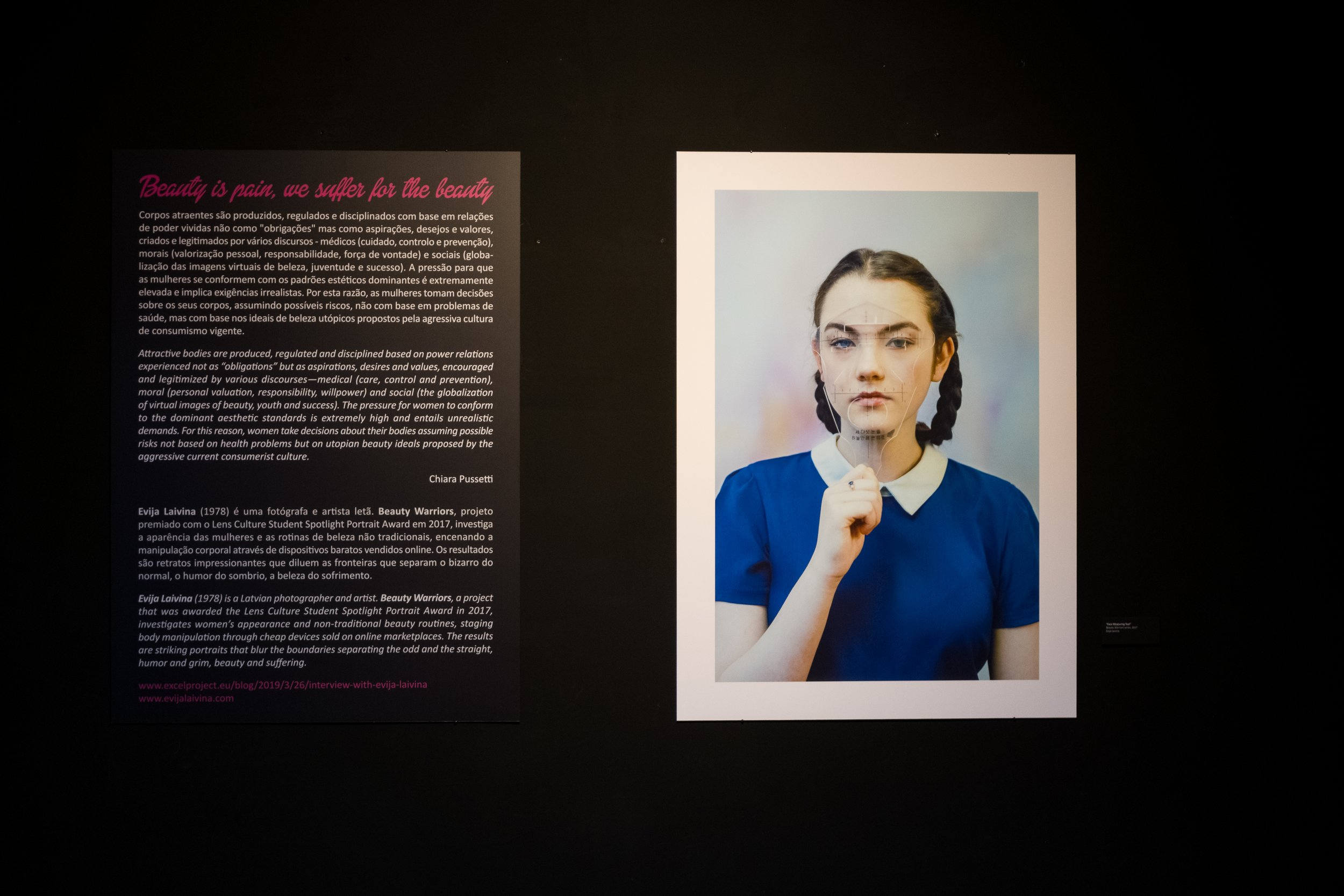

The exhibition featured experimental and undisciplined artistic interventions by the anthropologists involved in the project and the very subjects of the research (mainly installations, short films, multisensory experiences), and it had the collaboration of the multi-award-winning artists Evija Laivina (http://www.evijalaivina.com) and Jessica Ledwich (www.jessicaledwich.com). Our common ambition was not to propose an artistic overview of the scientific results of our ethnographic research. Rather, it was to provoke reactions, to discuss the expectations we have about our own bodies and others’ bodies, and to dramatize our daily “aesthetic entrepreneurship” (Elias et al. 2017, 5). In turn, the exhibition made our work more accessible and also more accountable. The provocative and ironic photography projects of Evija and Jessica emphasize that women are engaged in a relentless war against themselves throughout the course of their lives.

The battlefield is the female body. We are all “beauty warriors,” quoting the title of Evija’s project, to tap into an ideal of femininity that Jessica describes as the “monstrous feminine.” With a strong feminist and critical gaze, their photographic projects made an essential contribution to rethinking the ways in which we experience our corporeality and to reflecting on the violence of aesthetic ideals that reproduce structures of inequality and differentiation in the age of perfection.

With both Evija and Jessica, the encounter was fortuitous. To our surprise, we were each critically reflecting on the same issues of body image politics at the same time, and we shared deeper intellectual, theoretical, and even political concerns. During the research process, we conversed and thought together, engaging with texts and images as equal and interrelated modes of anthropological knowledge production. The main topics of the project—physical appearance, beauty standards, and the power of looks—demanded the use of images to stimulate reflection about the complex relationships between social media, visual culture, self-representations, body politics, and contemporary identity. The last few decades have been accompanied by massive shifts in digital and biomedical technologies of body modification and body image. My fieldwork was based on the evidence of the image-body inseparability, which includes idealized body images, self-representation, appearance, social exposition, body projects, and self-reconfiguration. Social media—combining text, audio, video, and images—are multimedia data that play a critical role in people’s self-image by informing and reflecting what they consider to be beautiful or attractive. Online images and their circulation inspire the construction of similar body ideals to be achieved through bodywork, body care, and body discipline. Through the exhibition, we aimed to demonstrate the image/body inseparability and interdependency, capturing the dual process of consuming images of the ideal body while transforming the body into those ideal images for consumption.

In the exhibition, we attempted to reproduce the multiplicity of imaginaries and virtual representations of the ideal type present in social networks, evoking the contemporary predominance of the visual. In an era when technology enables and encourages instant sharing, viewing, and duplicating, the images depicted the possibility of self-reconfiguration and the body’s transformation into a material to be watched, displayed, and consumed. First, we developed an online platform that enabled multimodal forms of knowledge construction by curating a collection of personal narratives, artistic experiences, field diaries, interviews, geographical maps, photographs, sounds, and videos as a space for anthropological debate and innovation (excelproject.squarespace.com). Next, we organized an exhibition combining photographs, texts, short film clips, audio, illustrations, fieldnotes, and material objects as different layers in order to engage a wider audience. In this way, we hoped to create a compelling aesthetic-political potentiality that might challenge the public’s way of seeing.

By Evija Laivina (Beauty Warriors). Poster design © terraesplendida.com.

By Jessica Ledwich (Monstrous Feminine). Poster design © terraesplendida.com.

In the gallery space, images and text alternated to reproduce an effect similar to that of Instagram posts. In an Instagram post, neither captions nor images are a mere transcription of the other: text and image can evoke an ironic contrast, creating tensions and allowing different interpretations. Images can be used as narratives to make statements about the body—illustrating its more intimate realities, tensions, and politics. The images can reinforce or challenge the text, creating “discordant meanings and unsettling our accounts of the world” (Poole 2005, 160). We were interested in the photos’ capacity for disruption and subversion of reality.

Evija’s photographs display women in classic poses, elegant and serene in their immobility, wearing beautification devices that look like instruments of torture. The models wearing these body-shaping devices stare off into space, appearing to obediently adhere to the conformity and discipline demanded by society, while the plastic devices frame their physiognomies in a grotesque manner. The strength of Evija’s portraits, for which the artist’s friends and family members have posed, lies in their ability to create a critical reflection on the suffering involved in the struggle to achieve a perfect body.

By Evija Laivina (Beauty Warriors). Face Lift Band.

By Evija Laivina (Beauty Warriors). Face Slimmer.

By Evija Laivina (Beauty Warriors). Eyebrow Stencil.

But the text accompanying the series of photos reminds us that “Beauty is pain: we suffer for beauty.”

Photo by Pedro Rebelo Pereira. Beauty is Pain.

Evija begins her work by acquiring online (via transnational markets such as eBay and Amazon) products, technologies, devices, and instruments designed to mold and contain the body within the distressed parameters of ideal beauty. She chose the cheapest tools, promoting the “quick-fix” idea—uplifting eyes, eliminating double chins, or amplifying smiles. Her portraits—in the space of imagination that lies between irony and violence—intend to denaturalize our global quest for “better” bodies, alluding to invasive and violent orthopedic disciplinary procedures, thus making the process by which we produce human beauty particularly disturbing. With provocative images of bodies constrained by corrective devices, she reveals the mise-en-scène of femininity, which is only achieved through disciplinary practices of controlling the size, shape, surface, and movements of the body, and then displaying this body as an ornamental element.

By Evija Laivina (Beauty Warriors). Everything is Awesome.

Moreover, Jessica’s photos oscillate between the grotesque and the absurd. Using her own body as a canvas, Jessica explores the monstrous things women do to themselves in the pursuit of beauty and perfection. In one photo, she buffs her leg with a Bosch sander; in another, she squeezes her flesh into control pants, only to have it mushroom out in other areas.

By Jessica Ledwich (Monstrous Feminine)

Jessica explores the uncanny, the abject, and often the irrational to unmask the more complex side of human behavior, analyzing its perversities to distill this strange phenomenon we call “culture.” “Am I perfect now?” This question echoes in every image Jessica produces. The audience poses the question to themselves, observing Jessica’s disturbing images. Beauty at any cost entails suffering, sacrifice, effort, discipline, and risks. Jessica, who has a completely normative appearance (she is young, tall, thin, and white, with a harmonious and symmetrical physiognomy), shows in her Monstrous Feminine project that even a mainstream, conventionally beautiful woman pays high economic, psychological, and physical costs to adhere to very exclusive standards.

By Jessica Ledwich (Monstrous Feminine)

We are all constantly bombarded by messages that reinforce the need to “discipline” and “tame” our body—its forms, weight, smells, fluids, appetites, contours, excrescences, the skin that covers it—in order to bring it closer to an “ideal” of beauty and femininity that, in reality, few women fit. There is a strong normative pressure to engage in what we define as “beauty work”: an activity in which one is supposed to invest considerable amounts of time and money in order to meet very restrictive beauty standards that, at least in the Euro-American context, value an elegant, pleasing, discreet, delicate figure that occupies a tiny space and does not disturb too much. For a woman to be socially considered worthy of approval and respect, she has to correspond to characteristics considered truly feminine on the basis of a standard model of beauty from which anything else is a deviation. The “other bodies”—non-white, non-young, non-thin, non-cisgender, non-able-bodied, non-normative in their functions—are reduced to “defects” that need to be corrected, reinforcing preexisting structures of inequality, differentiation, and discrimination.

Wrinkles, body fat, cellulite, sagging skin, hair graying, skin spots, and every other physical change that accompanies aging should be fought with the energetic maintenance of the body through medical-aesthetic, cosmetic, fitness, and “health food” industries (such as diets, superfoods, and miraculous supplements). The beauty industry reminds us that if only you were thinner, firmer, smoother, and younger, you would be better; you would have a more passionate relationship, a better career, more friends and success; you would be happier. If you are unable to “repair,” to “correct,” to “fix” your aesthetic “problems,” and to “solve” the signs of bodily aging, you should consider yourself a failure. Women are told that they are unstoppable: they can change or obtain anything they desire with sheer willpower. It depends entirely on them: with willpower and discipline, nothing is impossible.

During the four years dedicated to this research, I interviewed women willing to do anything to achieve utopian standards of perfection and success:

to mould, transform, and cut the flesh;

to smooth, lighten, and burn the skin;

to compress and mechanically absorb fat;

to ingest and inject drugs, toxins, hormones, and other liquid biotechnologies;

to insert prosthetics and implants;

to undergo extreme surgery or create body curves with industrial silicone.

Women here are at “war”—to win the battle against time, combat cellulite, defeat fat, and ultimately conquer the ideal physical form. Women fight against their own bodies: the more they work to make them socially acceptable, the more they become controllable and better consumers of an industry that thrives on their insecurities. It can seem like a perpetual battle, like fighting against a windmill, but this is a war we can lose by surrendering to the reality of a body that does not conform to social expectations. This is a war in which one can die if they choose not to surrender.

Evija’s Fat Series disconcerts and embarrasses the audience, because the fat feminine body represents the lost battle, the surrendering body, and the real deviation from the norm.

By Evija Laivina (Fat Series)

By Evija Laivina (Fat Series)

By Evija Laivina (Fat Series)

Few things are as frightening as a woman who occupies too much space, who feeds excessively, who follows impulses and satisfies her desires, who transgresses the norms, who exceeds the space allotted to her, who does not control her bodily excrescences (such as nails or body hair), who expands beyond the rigid limits that society imposes. The fat woman responds to a triple accusation: lack of attractiveness, lack of control, and lack of responsibility over their own health. If men are also targets of fatphobia, the most affected of all are, once again, women. That is why women are more vulnerable to developing eating disorders. As such, the photographs show the model’s pale body constrained in shapewear, waist trimmers, and constricting bands.

While I was collecting narratives of women fighting against weight in search of perfection, I came across the news of a young girl’s death in my hometown in Italy. Beatrice, just 15 years old, threw herself under a train with her school bag on her back. According to the letter that she left to her parents, she wanted to end the pain of nonconformity, rejection, and peer judgment. She was compelled to suicide because she was considered fat. She hated her body, with its overflowing flesh that refused to fit into the measurements imposed by an obsessive culture of appearance. I suddenly remembered my high school days, in the same city, in the same school Beatrice was attending, the same train line I crossed every day, the same looks that evaluated and judged me, the same fear of not being thin or pretty enough.

Suddenly Beatrice’s story became my story, my daughter’s story, my thin friends “against their body’s nature,” the ones who struggle to burn calories, who eat as little as possible to be light as feathers, who develop eating disorders that can lead to death, who struggle to contain their shapes in that XS space that society inflicts upon us. This is the story of all the people whose corporeality contradicts—in its proportions, volumes, and contours—the ideal of the perfect body. This is the story of all the victims of the perfectionism trap. The very victims are not only the people who have lost their lives because of complications during plastic surgery or post-operatively but also those who develop body dysmorphia, eating disorders, or depression and who suffer because they do not fit into the rigid limits and forms of the hegemonic body norm. In particular, the victims are young people, such as Beatrice, who are particularly vulnerable to the imperative of the perfect body.

Movies, commercials, magazines, social media accounts, and websites often portray stereotypically beautiful, thin people as ideal. Adolescents are constantly exposed to thousands of overt and subtle messages about the “ideal” body and unrealistic, unattainable portrayals of beauty. They see the world through filters, digital manipulation, and augmented reality that have made “perfection” completely artificial. So young people are comparing themselves to ideals that do not exist in reality. If they do not perfectly fit society’s standards, they are not enough. But this is a losing battle: they will never be enough because the parameters are constantly being redefined, shifting in line with trends and the interests of the beauty industry. The discrepancy between the ideal and the real creates dissatisfaction, suffering, and fear. And in a capitalist society, both equate to opportunities for profit. Teens, in particular young girls, are easy victims of an industry that flourishes by making us feel wrong, ugly, deviant, inadequate, and imperfect.

When Evija and I selected the picture for the promotional poster of the exhibition, our choice fell on the image of a young and absolutely perfect girl. Being mothers, observing our daughters, we both have the impression that young people are particularly susceptible, as they are in a developmental phase where they experience both pubertal and identity changes. Girls are especially in danger of internalizing sociocultural values of appearance, trying to correspond to their own perception of boys’ expectations of the female body after they too have been exposed to idealized media images. Society’s unrealistic beauty ideals create an immense sense of pressure on girls to achieve a perfect body, emphasizing the importance of physical attractiveness as an evaluative key aspect of femininity. Adolescence is the period when young girls (and boys, too, of course) begin to mold their physicality and domesticate their appearance—starting with diets, hair removal, manicuring, going to the gym, and so on—as beauty warriors fighting to conquer an ideal femininity that Jessica describes in her defiant photographic project as “monstrous.”

Over a month, the gallery turned into a privileged laboratory for experimentation. Each week we organized at least three debates, workshops, or other events open to the public. The purpose of these meetings was to create an experimental space that would bring into dialogue social scientists, artists, students, the subjects of our research, and the public. In particular, our aim was to reach young people, to reflect with them on their own processes of bodily subjectification, problematizing discriminatory beauty ideals that classify and hierarchize bodies—differentiating who counts as beautiful and valuable and who is “defective” or not normative. We wanted to reflect together on the impact of global mainstream images of idealized bodies that inspire our bodywork and beauty labor in order to reproduce bodies congruent to that ideal type—involving high school and university students. The connection with the public was instant. The originality of the activities that took place in the gallery lies in the many possibilities of experiencing the exhibition in its different dimensions and layers. The photos, like the videos and objects, were not conceived of as documentary materials of the research but rather proposed as methodological devices for collaborative “meaning-making.” The impact of both Evija’s and Jessica’s humorous and shocking images, as well as the very materiality of the technologies used in aesthetic medicine and plastic surgery, has proven to be excellent devices to raise discussions and receive viewers’ reactions and comments. The images exposed became the ground for the sharing of aspirations, anguishes, and emotions, and the interactive encounters in the gallery unveiled the dynamic and dialogical nature of knowledge. The very materiality of the fieldwork—with its liquid and gelatinous injectables, futuristic prostheses, silicone gel or saline-water-filled implants, bandages, and shapewear solutions—gave rise to epistemic objects that encourage visitors to reflect on the limits and risks associated with the pursuit of perfection. The public was invited to literally touch and experiment with the biotechnologies that are commonly used to alter our bodies according to hegemonic ideals of beauty and perfection, exchanging their unique experiences among them.

Photo by Pedro Rebelo Pereira, Delicatessen, Artist: Chiara Pussetti.

Photo by Francesco Dragone, Delicatessen, Artist: Chiara Pussetti.

Photo by Pedro Rebelo Pereira, Touch Me Now, Artist: Chiara Pussetti.

The public also spontaneously participated in the exhibition by inserting artifacts into the gallery, weaving their individual experience into the narratives already present. For example, the installation Getting out of the Fu**ing Closet, which initially resulted from a series of workshops entitled “The Hacked Barbie” (in which participants recreated themselves by modifying dolls as symbols of hegemonic beauty), was expanded to the public during the exhibition period by accepting new contributions and newly hacked dolls. “The Hacked Barbie” workshops and dolls illustrated many unexpected bodily biographies and processes of subjectification, narrating stories of eating disorders, aging, post-partum depression, surgical interventions, stretch marks, and so on. The public itself was included not as a passive viewer but rather as individual, active participants in producing the dolls, sharing their experiences in order to birth new forms through the co-construction of knowledge. Thus, alongside Jessica’s and Evija’s photographs, several “Hacked Barbies” appeared in the exhibition, showing the reality of lived bodies. The doll’s perfect body was modified to remark—with skin-deep scars—real-life stories, embodied biographies made up of suffering, violence, and contradictions. The modifications represented embodied narratives, in which personal desires and anxieties become embedded in action. The uniqueness of each individual somatic experience is enriched by the resonances with the other stories. In Getting out of the Fu**ing Closet, the Barbies forced us to hold up a mirror and ask questions about ourselves.

Photo by Pedro Rebelo Pereira, Getting out of the Fu**ing Closet.

Photo by Francesco Dragone, Getting out of the Fu**ing Closet.

Photo by Pedro Rebelo Pereira, Artist: Chiara Pussetti.

Photo by Pedro Rebelo Pereira, Artist: Barbara Pisco.

The incorporation of the public in the creative art-inspired and art-making practices was made possible by using approaches from anthropology that emphasize the interactions among artists, audiences, and participants—a method that I have elsewhere called “art-based ethnography” (Pussetti 2018). The public interacts with the objects, creating new interpretations, posting images and comments online, producing new artworks. This process of understanding continuously brings into play our senses, our imagination, our emotions, our collective imaginaries and unconscious expectations (Edwards 2006; Elliott and Culhane 2016; Pink 2006).

Photo by Francesco Dragone.

Photo by Francesco Dragone.

Photo by Francesco Dragone.

Following the suggestions of Anna Grimshaw (2001), I consider that artistic practices, the tangible materials of installations and the interaction with the public, are constitutive of the very ethnographic goal of the co-construction of knowledge. This research process continued during the exhibition, transforming the gallery into a space of collective interpretation and reflection. In recent years, a growing literature on the potential of intersections between “art” and “anthropology” has been reshaping the debate on knowledge production and ethnographic methods and practices. Much of this literature advocates a stronger engagement with a sensorial, emotional, person-centered, and postcolonial representations of the field, instigating discussions about how creative or experimental collaborations between ethnographers, interlocutors, artists, and the general public can be valuable in the research process.

The collaboration with people outside the social sciences in the very conceptualization process of this exhibition, as well as the relationship with the public, has enabled us to generate new reflections and insights on body-making processes. The body carries with it a dense history of meanings regarding race, class, gender, sexuality, disability, and age. The conversations with the varied audience present during the several organizing meetings highlighted how cosmetic procedures and daily-use beauty products reinforce hegemonic (and very exclusive) body-norms, in which only few people fit. The life stories collected throughout the research process, which included artistic production and the relationships established with the public during the exhibition, reveal that there is nothing superficial about body appearance or beauty. That is why they matter so much. There is nothing futile about something for which people are willing to invest time and money, to suffer, to put their lives at risk. There is nothing futile in technologies of biopower, which distinguish people between those who have value and those who do not. There is nothing futile in knowing that our children will grow up—as we did—cultivating desires on the basis of unrealistic ideals that constantly make us feel inadequate.

The work I have done in recent years is nourished by the hope that, in the near future, we will be able to make our ideals of beauty more comprehensive, varied, and inclusive so that each person can be as they are, in their specificity, feeling beautiful and sensual, loving their image in the mirror, occupying the space they want in the world, with freedom. The main purpose of this volume is to remind everyone that being tall, short, thin, fat, white, black, straight, gay, cisgender, transgender, etc., is something that happens and about which we can do nothing. We have no real choices here, because we cannot choose to be who we are not. Being people who respect others is a choice we can make, and it is within our reach. The time has come to take a stand and make this ethically conscious choice, by understanding biases and making changes. My hope and goal with this work is to stand up against body shaming, lookism (appearance discrimination), and all the systemic, disrespectful attitudes that allow the cosmetic industry to thrive and promote gender inequality.

Photo by Francesco Dragone.

Short Film

https://vimeo.com/804598652

Director and cinematographer: Francesco Dragone

References Cited

Azoulay, Ariella. 2008. The Civil Contract of Photography. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Edwards, Elizabeth. 2006. “Travels in a New World—Work Around a Diasporic Theme by Mohini Chandra.” In Contemporary Art and Anthropology, edited by A. Schneider and C. Wright, 147–56. Oxford: Berg.

Elliott, Denielle, and Dara Culhane. 2017. A Different Kind of Ethnography: Imaginative Practices and Creative Methodologies. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Grimshaw, Anna. 2001. The Ethnographer’s Eye: Ways of Seeing in Modern Anthropology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pink, Sara. 2006. The Future of Visual Anthropology: Engaging the Senses. Oxford: Routledge.

Poole, Deborah. 2005. “An Excess of Description: Ethnography, Race, and Visual Technologies.” Annual Review of Anthropology 34:159–79.

Pussetti, Chiara, ed. 2018. “Art-Based Ethnography: Experimental Practices of Fieldwork.” Visual Ethnography 7 (1).

Pussetti, Chiara. 2021. “Because You’re Worth It! The Medicalization and Moralization of Aesthetics in Aging Women.” Societies 11 (97): 1–16.

Pussetti, Chiara, and Alvara Jarrín, eds. 2021. Remaking the Human: Cosmetic Technologies of Body Repair, Reshape and Replacement. Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Pussetti, Chiara, Elaine Reis Brandão, and Fabiola Rohden, eds. 2020. “A Indústria da Perfeição. Circuitos Transnacionais nos Mercados e Consumos do Aprimoramento Cosmético e Hormonal.” Revista Saúde e Sociedade 29 (1).

Pussetti, Chiara, Fabiola Rohden, and Alejandra Roca, eds. 2021. Biotecnologias, transformações corporais e subjetivas: saberes, práticas e desigualdades. Portalegre: ABA, UFRGS Edições.

Note

[i] The EXCEL project was funded by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) (PTDC/SOC-ANT/30572/2017), and coordinated by the author at the Institute of Social Sciences at the University of Lisbon.