Media, Mediumship, and the Supernatural

By Nadia Mbonde (NYU)

When examining the nature of media, we must ask if media is merely a product of the human will to communicate or if it possesses its own agency. As a neurodivergent astrologer and tarot reader with a general fascination with the occult, I have a scholarly interest in knowledge production that acknowledges the agency of immaterial forces in human life and unifies—as with the term “supernatureculture”—unfruitful Cartesian divides (Fernando 2017). Interspersed between my examination of media and the supernatural, I employ a visual vocabulary to capture my experience with the supernatural that cannot fully be expressed in words, with image descriptions for accessibility.

Nadia’s silhouette dancing down a hill, sending salutations to a shooting star beaming across the night sky emitting from her third eye.

What if “humanity is the medium of media rather than the other way around” (Boyer 2007, 25)? Drawing on media historians and social theorists to understand the material and social conditions that produce the aliveness of media, I propose that media is inseparable from the supernatural. In line with Hegelian philosophy, which conceptualizes “everything in the world to be the medium of an immanent divine force” (Boyer 2007, 31), media can be conceptualized as a force in and of itself that transcends human consciousness. Humans use media because most of us are not capable of telepathy. Media serves as a semiotic conduit for messages that we cannot understand without a mediating object. Media is ontologically entangled with mediumship. Synonyms for media, such as medium, conduit, and channel, are used to describe spiritualists, clairvoyants, and readers, who claim to convey messages between humanity and the spirit world. Thus, studying human mediating objects provides key insights into how nonhuman mediums operate.

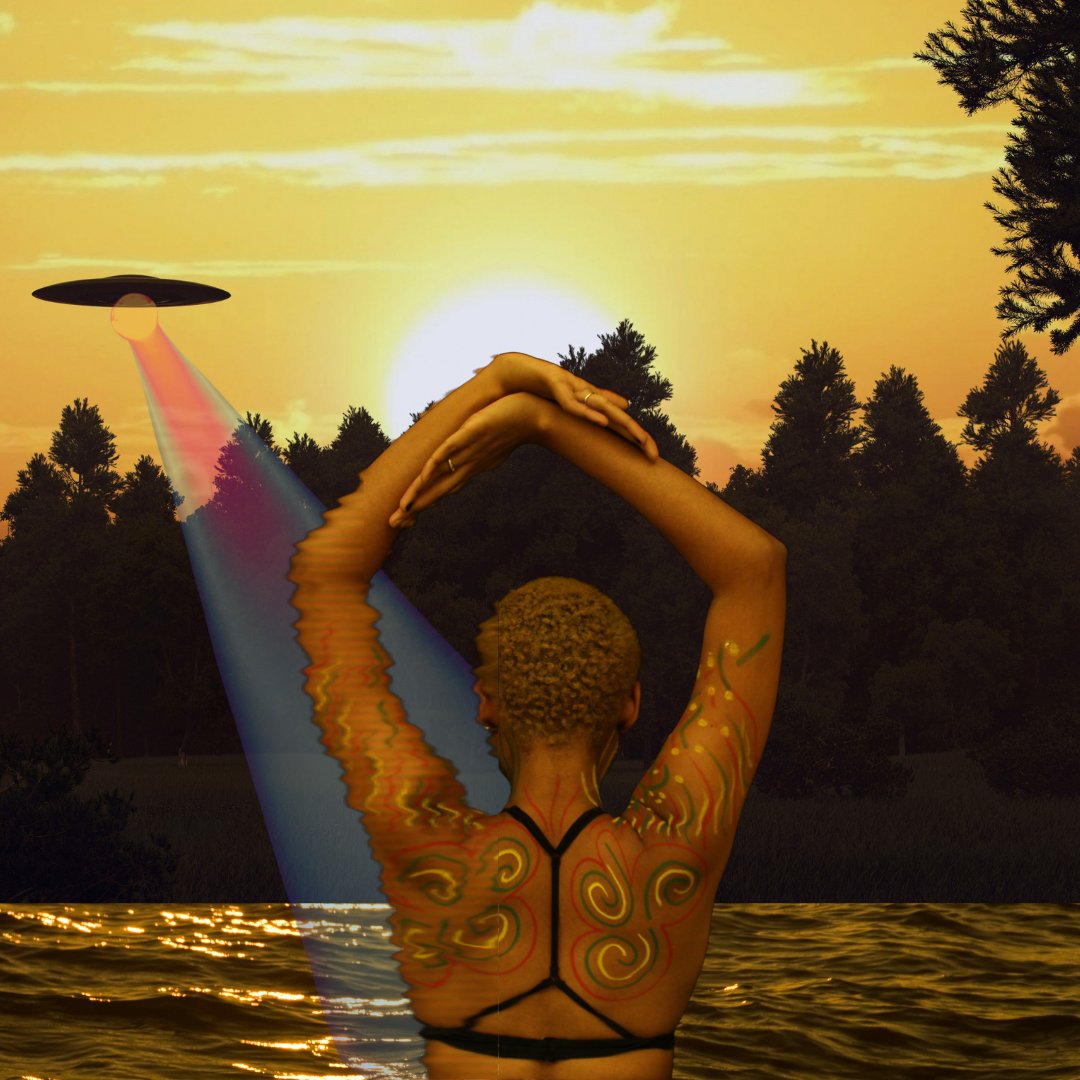

Against the backdrop of water, forest, and a sunset, Nadia salutes a UFO as she gets abducted.

The relationship between media and mediumship reveals that media cannot be separated from a paranormal world beyond human comprehension or from material and social conditions created by race, gender, and class politics. Human mediums perform labor similar to telecommunication media. Developed by German doctor Franz Mesmer in the eighteenth century, mesmerism harnessed newly discovered magnetic and electrical forces to access distant temporal and spatial planes (Jackson 2010, 282). Paschal Randolph, a nineteenth-century African American mesmerist, used his “negatively ‘vampiric’ powers of spirit mediumship” to escape slavery and aid the abolitionist cause (Jackson 2010, 281). He channeled messages from historical figures, such as Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, Martin Luther, and Socrates, about the injustices of slavery and oppression of women. This is illustrative of how media has always served as a vehicle for mediating political assertions, as with the contemporary circulation of videos and images of deceased civil rights leaders during Black History Month, for instance.

A black-and-white image of Nadia wearing orange flower petals as wings while holding a crystal ball. Behind her is the New York City skyline reflected in water.

The Spiritualism movement of the nineteenth century exemplifies the historic relationship between media and the spirit world. In 1844, Samuel Morse invented telegraphy, the first long-distance means of electronic communication. Spiritualism, a religious practice of communicating with the dead, “explicitly modeled itself on the telegraph’s ability to receive remote messages” (Peters 2001, 94). People believed that the dead communicated with the living through the “spiritual telegraph,” which was not merely a metaphor but an actual “technology of the afterlife” (Sconce 2000, 12). The telegraph was imbued with the supernatural, an entity that was neither neutral nor universal. Instead, it was marked by class, gender, and race, as evidenced by those who could afford it as well as the epithet “hysterical telegraphy” (Sconce 2000).

Nadia levitates from an ocean storm into a large cloud of smoke. The top left reads, ‘A PERFECT STORM’ and on the bottom right is a TIME headline that reads, “COVID-19 May Be Linked to Spontaneous Psychosis.”

Most mediums of the nineteenth-century Spiritualist movement were white women who presented themselves as technological devices linking the “living and the dead, science and religion, masculine technology and feminine spirituality” (Sconce 2000, 54). In the nineteenth-century United States and Europe, hysteria was deemed a disease of civilization, explaining white women’s frailty and causing their psychological and gynecological ailments (Briggs 2000). Men used accusations of hysterical telegraphy to prevent women from rivaling them in their political power and taking on social roles outside the home. Mediums who threatened the status quo of “traditional religion and rationalist science” became vulnerable to accusations of insanity and subsequent stigmatization, institutionalization, and even death (Sconce 2000, 13).

A lunar halo illuminates Nadia against a starry night’s sky. Northern lights dance above her, bleeding into an upside-down silhouette of a dark forest.

The portrayal of female mediums as hysterics produces a relationship between media and madness. The conceptualization of telecommunication media as an extension of humankind’s cybernetic nervous system becomes pronounced when people consume media while in altered states of consciousness, as with “the delusional viewer who believes the media is speaking directly to him or her” (Sconce 2000, 3). In psychotic states, viewers of media find that it assumes a “sentient quality,” achieving the desired effect on behalf of the media industry to profitable consumers that, be it the radio or television, is an “intimate interlocutor engaged in direct contact with its (psychotic) audience (of one)” (3). Thus, the “liveness” of electronic media “leads to a unique compulsion” that blurs the boundaries between the real and unreal (3–4). Our direct conversations with virtual assistants like Siri and Alexa have led some to argue that we as a society may be entering a repressed psychotic state (Sconce 2000). This phenomenon can be seen in the romantic relationships people form with AI companions, like Replika, which are designed to “always [be] here to listen and talk” and are “always on your side” (replika.com). This is also evident in the emergence of electropsychopathology, where media addicts, such as gamblers and gamers, are enticed by a “living electronic connection so alluring [that they] shun the real world in favor of cyberspace” (Sconce 2000, 304).

A static image of Nadia looking shocked while wearing spoons in her hair appears on a TV screen.

The relationship between humans and cameras offers insight into the way media has often been seen as an ideal medium for human aspirations of immortality. Spiritualists believed that communication from supernatural entities could be conveyed through daguerreotype, the first commercially viable photographic process of the 1840s and 1850s. This led to “spirit photography,” exemplified by William Mumler, who accidentally produced a self-portrait that seemed to show the ghost of his cousin. Rather than revealing this accidental invention through long exposure and superimposed negatives, Mumler allowed Spiritualists to believe that his camera could capture ghosts. Like telegraphy, Spiritualists used spirit photography as “scientific” evidence of a community of the dead in the afterworld serving the function of documenting the objective existence of spirits, entertaining phantom enthusiasts, and comforting mourners. According to Roland Barthes (1981), “all photographs are like spirit photographs” (quoted in Jackson 2012, 282)—only in this case, the ghosts are ourselves. In other words, photography is “an attempt to watch ourselves dying” (Jackson 2012, 282–83). By documenting how we age and signs of our impending demise, film and photos index our frail mortality. They provide evidence that we were once alive, even after we are long dead.

A black-and-white image of Nadia dripping wet looking down at a source of light. A smaller image of Nadia holding a candle appears on each shoulder.

Sylvia Martin (2016) demonstrates the arresting force of the camera in the production of death scenes in the Hong Kong film industry, which are believed to have supernatural risks, including spirit possession. The affective labor involved in the reenactment of death is “spiritually provocative,” making the actors, stunt workers, and production personnel vulnerable to predation by gwei, mischievous spirits “who may be drawn to the spectacle of death and violence” and haunt the performers (2). As mediums themselves, the film crew and performers “labor between the worlds of life and death” and thus are given lai see, a form of payment given to protect the performance and invite “good fortune” (3). Tejaswini Ganti shows how media indexes the “symbolic construction of reality” linked to ritual, mythological, and cosmological issues (Coman 2004, 2). Ganti (2012) describes cine-magic in the Hindi film industry, where rituals are used to reduce risk of misfortune. For instance, important film production dates are scheduled using mahurat, which is “an astrologically calculated auspicious date and time to start any new venture” (248). Thus, it is clear in the contexts Martin and Ganti evoke that media practices must be conceptualized in tandem with the agency of nonhuman forces.

Nadia’s legs in olive skinny jeans and beige stilettos being consumed by a blue galaxy in outer space.

Studying the relationship between media and mediumship can help us understand how humans interact with and produce media. Humans can be seen as mediating objects of nonhuman entities, which can lead to the cybernetic production and exchange of ideas. By looking at the mechanistic aspects of how media is created and how humans respond, we can conceive of elements of our interaction with media in which humans are not entirely in control. Though limited, a gender analysis in media history has been done; however, more work is needed to include race, class, disability, and mental illness. The discourse of transhumanism and Afrofuturism can shed light on the material conditions that produce media. This scholarship can help us understand the rapidly advancing technological age and its relationship to existing infrastructure built during slavery and the colonial period.

References Cited

Barthes, Roland. 1981. Camera Lucida. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Boyer, Dominic. 2007. Understanding Media: A Popular Philosophy. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press.

Briggs, Laura. 2000. “The Race of Hysteria: ‘Overcivilization’ and the ‘Savage’ Woman in Late Nineteenth-Century Obstetrics and Gynecology.” American Quarterly 52 (2): 246–73.

Coman, Mihai. 2004. “Media Anthropology: An Overview.” Media Ethnography Online Working Group, 2004–2005.

Fernando, Mayanthi L. 2017. “Supernatureculture.” SSRC The Immanent Frame, December 11. https://tif.ssrc.org/2017/12/11/supernatureculture.

Ganti, Tejaswini. 2012. Producing Bollywood: Inside the Contemporary Hindi Film Industry. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Jackson, John L., Jr. 2010. “On Ethnographic Sincerity.” Current Anthropology 51 (S2): S279–87.

Jackson, John L., Jr. 2012. “Ethnography Is, Ethnography Ain’t.” Cultural Anthropology 27 (3): 480–97.

Martin, Sylvia. 2016. Haunted: An ethnography of the Hollywood and Hong Kong Media Industries. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Peters, John Durham. 2001. “History of An Error: The Spiritualist Tradition.” In Speaking into the Air: A History of the Idea of Communication, 63–108. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sconce, Jeffrey. 2000. Haunted Media: Electronic Presence from Telegraphy to Television. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Cite As

Mbonde, Nadia. 2023. “Media, Mediumship, and the Supernatural.” American Anthropologist website, May 19.