Welcoming Migrants with Dignity… Until We Couldn’t

by Alyssa Goldstein Sepinwall (California State University)

“Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door.”

--Emma Lazarus, The New Colossus, 1883

“America’s sovereignty is under attack. Our southern border is overrun by cartels, criminal gangs, known terrorists, human traffickers, [and] smugglers….

It is my responsibility as President to ensure that the illegal entry of aliens into the United States via the southern border be immediately and entirely stopped.”

--Donald Trump, Executive Order, Jan. 20, 2025

This is a story from the border city of San Diego, of social service agencies and citizens working to welcome migrants with dignity … until the second Trump administration repudiated the ideal of the US as a nation of immigrants and closed the border to asylum-seekers. This is also my story, of a scholar-citizen trying to alleviate, at a human level, problems I knew about from my research, in the most feasible and trauma-informed way… until the 1/20/25 Executive Order ended this work. My story moves from despair to rage to heartbreak to hope – before ricocheting back in reverse.

* * *

Choosing to volunteer with an NGO, feeding people and translating for them, was not a self-evident process for me. As a scholar of Haiti, I am all too aware of the problems with “humanitarian aid.” Scholars like Alex Dupuy, Paul Farmer, Nadève Ménard, and Mark Schuller have helped me understand that international policies toward Haiti have created systemic inequalities that no foreign NGOs or busload of volunteers can reverse.[1] These ideas were reinforced for me by Raoul Peck’s film Fatal Assistance (2013), which explored the abject failure of foreign efforts to reconstruct Haiti after the 2010 earthquake, as charity funds went to foreign NGO workers’ rent and salaries while providing little real help to Haitians. I also translated for publication a speech Peck gave at a 2014 conference in Frankfurt, entitled “Beyond Help.” I have sat deeply with its warnings about how the “assistance armada” reinforces the inequalities produced by global capitalism, while doing “nothing more than play the role of a big bandage around open bellies.”[2]

Because of this knowledge, I’ve been skeptical of foreign aid efforts in Haiti. Haitian friends have advised me that I can best help Haiti from abroad by using my knowledge as a historian to advocate for changes in US policies that have stripped Haiti of sovereignty (imposing regimes answerable to Washington instead of to Haitians) and that continue to impoverish it. So after protests began in Haiti in 2018 (with citizens challenging the corruption of the ruling PHTK party) and especially after the 2021 assassination of Haitian President Jovenel Moïse, I sought to amplify Haitians seeking to create a new Haiti. As they pushed for true sovereignty under a new generation of leaders, I did media interviews to publicize their efforts and urged journalists to interview them. I co-wrote an op-ed with Haitian civil society leader Emmanuela Douyon for the Washington Post, to encourage aid groups not to repeat fatal errors in Haiti; I was honored that our essay was cited in a filing challenging the Biden administration’s mistreatment of Haitian migrants.[3]

Unfortunately, American policies toward Haiti did not change in 2021-22; the PHTK used gang allies to assassinate opponents, and the numbers of Haitians fleeing mounted. Meanwhile, the Biden administration retained Trump-era policies (“Title 42” rules) that invoked COVID-19 to block asylum seekers from entering. I railed against Title 42 on social media; I highlighted President Biden’s hypocrisy in declaring COVID-19 over[4] while keeping asylum seekers out to “protect” Americans from it. But this activism, informed by my scholarship and by solidarity with asylum seekers, often felt futile.

On May 12, 2023, Title 42 rules were finally set to expire. Haitians and others from around the world, who’d been stranded and vulnerable in Tijuana and other border cities without being able to ask for asylum, began massing at the border. Scenes of families kept without food or water between two border fences, broadcast globally, were heartbreaking.[5] Unlike other humanitarian crises I might see on television, though, this one was local; I live in San Diego County, less than an hour from these fences.

My friend Nadève Ménard, professor at the State University of Haiti, once told me that acting to fix problems in my local community was more likely to be effective than trying to aid Haitians from afar. I turned to Pedro Rios, a Twitter friend and director of the AFSC US/Mexico Border Program, to ask how to participate in relief efforts. Rios recommended Jewish Family Services of San Diego/San Diego Rapid Response Network (JFS/SDRRN). He noted that they had an organized structure for volunteers and received clients daily (after migrants secured appointments to present their paperwork at the border, using an app called CBP One and were released).[6]

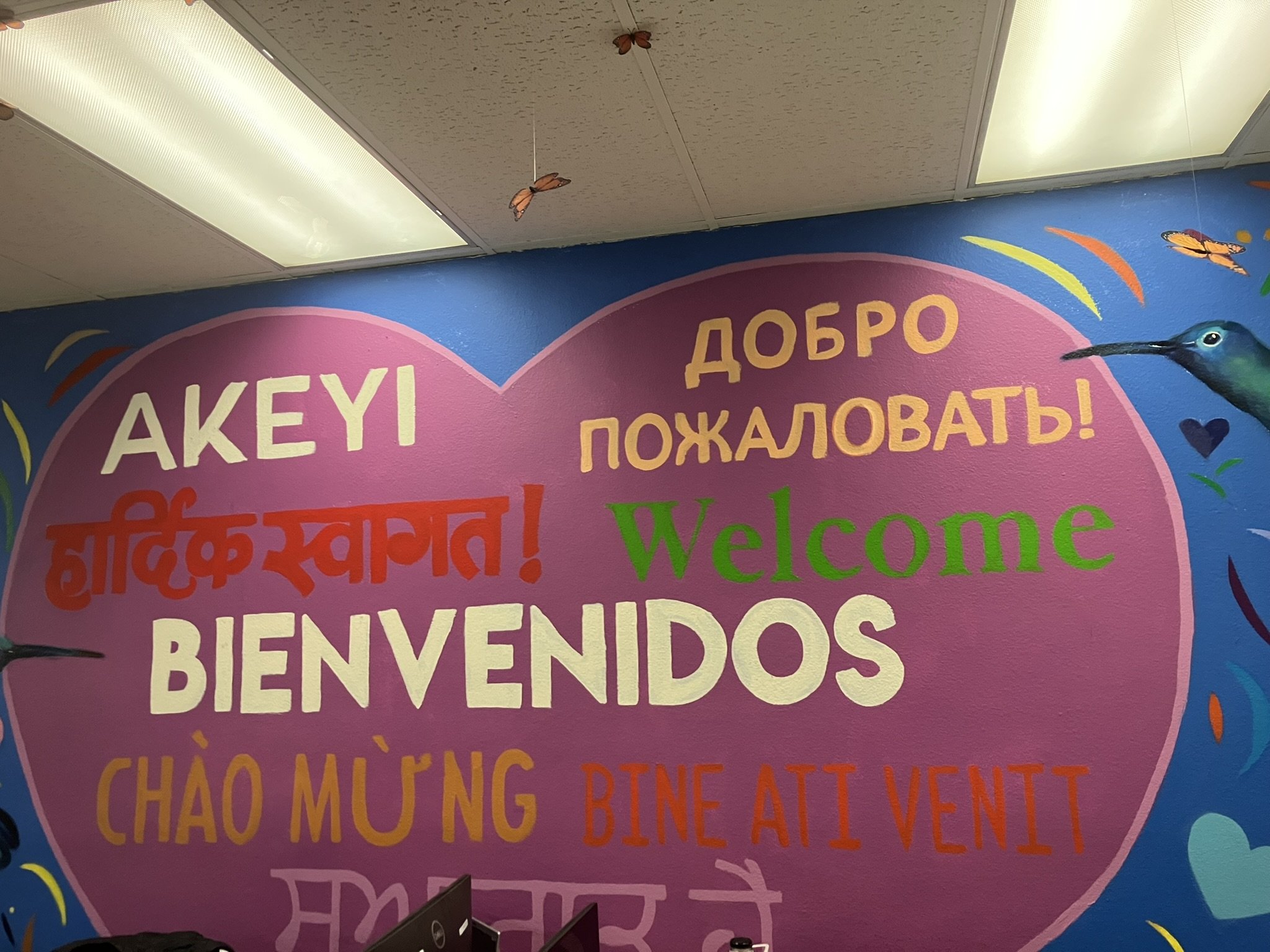

The welcome wall.

I contacted JFS and rushed to complete my volunteer application and undergo a background check. I had some special skills to offer and some more mundane ones. First, I could help Haitians by translating from French or Haitian Kreyòl. In San Diego, many speak Spanish, but few know those languages. Less skilled tasks also needed doing. While assembling snack bags could feel more inconsequential than translating, … people need to eat.

Just as the school year ended, I was cleared to work as a shelter volunteer and airport guide, alongside JFS’s professional staff. During my training, I saw that they worked long hours, 24/7, to care for migrants. Our mission was “Welcoming With Dignity,” growing from the Jewish value of Welcoming the Stranger. This resonated deeply with me, with a Canadian immigrant dad on one side and, on the other, a grandmother who’d fled antisemitic violence in Poland as an unaccompanied minor. Because we aimed to serve clients in their own languages, shelter staff were bilingual; many were immigrants or children of immigrants. The agency screened migrants for COVID-19 (providing medical care if needed); housed them and supplied them with food until they arranged travel; provided discounts in booking tickets to their sponsors around the US; and finally guided and translated for them through the airport. We were eager to help clients have a peaceful last leg of what had been, for many, an agonizing journey.

In my almost two years of volunteering, I met many inspiring people. They included elderly Russian Muslims; families fleeing violence in Guatemala, El Salvador, and parts of Mexico; transgender asylum seekers from Venezuela and Cuba; and lots of Haitians. I met Haitian engineers turned Mexican factory workers; people newly fleeing disorder in Port-au-Prince and others who’d lived in Latin America for years but faced violent discrimination; young Haitian men and women eager to continue their studies in the US; and other Haitians yearning to be reunited with sweethearts. I did not want to treat passengers as research subjects, so I did not set out to leave shifts with oral histories or ask questions that might cause trauma. But sometimes clients would share stories even when I asked superficial questions.

Part of the flag wall that greeted migrants in our waiting room, symbolizing the many different countries migrants came from around the world.

In weeks I worked at the travel shelter, I would mass-assemble snack bags (strangely relaxing compared to academic work), then head to the converted motel we operated to deliver them to client rooms. I only knew the number of people in a room before knocking, not their nationality. As a default, I greeted people with “Buenas tardes!” since many clients were from Latin America. But I was thrilled when I found Haitians on the other side of the door. Volunteering on days like January 1, 2024 (Haitian Independence Day), I could give a sense of home, wishing “Bòn Fèt Endepandans!” and adding wryly “m ap désolé li pa soup joumou!” (I’m sorry I’m not bringing pumpkin soup, the traditional Independence Day meal!). Being celebrated for being Haitian – after experiencing antihaitianismo in Latin America – brought palpable joy to clients, even if I only had pretzels, tuna, and applesauce. Some days I served lunch at the travel shelter, which was a great opportunity to meet Haitians and have longer conversations. I loved learning about travelers’ hopes for the future and where they were going; I would try to find Haitian community centers or ESL classes for them.

At the airport, I served whoever had been able to book travel that day; for languages we did not know, like Ukrainian or Pashtun, we used Google Translate. Sometimes I arrived at the airport with a Haitian flag (a symbol that Haitians are especially proud of, as the emblem of their Revolution). I was always delighted to find Haitians among my passengers and to see their relief at being spoken to in their own language, after they’d needed to be understood in Spanish for months or years. “How do you know Kreyòl?” they would ask. “Mwen renmen pale lang mwen” (I love to speak my language), one older woman exulted.

My goal during airport shifts was to make the evening easy. I wanted to transform the potential trauma of going through a checkpoint and to make clients comfortable. TSA knew our staff, and wanted most for us to ease their jobs by ensuring that clients knew to empty their pockets and not bring liquids. I would joke to passengers about how, at this checkpoint, they would not have money stolen – but god forbid if they tried to sneak through a bottle of water! I became familiar with the TSA agents at San Diego International, many of whom were the children of Latino migrants. Sometimes if I had Spanish-speaking travelers, they would explain better than my smiling but clunky “dinero, zapatos, cinturón… Todos aquí!” [gesturing to the conveyor]. I went through TSA alongside passengers; we would laugh when I sometimes forgot to remove my phone from my own pocket (absent-minded professor!).

My favorite part of airport nights was usually the moment after we cleared TSA. My clients saw that, as I’d promised, this was not a frightening checkpoint. The TSA agents returned all their possessions – except for large bottles of shampoo or cologne they had not thought to remove from carry-ons. I also loved it when I could get the check-in staff at United (the airline many clients used) to waive baggage fees if tickets didn’t allow for checked luggage – though many clients had only a backpack of possessions left, which was painful to contemplate.

As much as I aided clients, they were also helping me. Sometimes when they didn’t have passports and we spent a long time waiting in the I-94 (immigration paperwork) line, they would ask, “Why do you volunteer with migrants?” “Oh!” I would say. “My abuela was a migrante. She was helped by kind people, and I want to do the same for others” (I did not mention that stringent US immigration laws meant she could not get her family to safety, and that everyone except one nephew was murdered in the Holocaust). To Haitians, I apologized for the US support of the PHTK and the fact that they had to flee when they would have liked to stay in Ayiti cheri. I always parted from passengers at the gate by wishing them the equivalent of anpil siksè ak kontantman nan Etazini yo (much success and happiness in the US!) – and sometimes we hugged. I loved getting to practice languages; meet inspiring people who had suffered but were ready for a fresh start; and help people complete their journeys.

I knew, of course, that being kind and welcoming to each client did not change the systemic inequalities – or misguided US foreign policies – that pushed people to flee. Still, I wanted to provide a counterweight to government officials, gang members or unscrupulous civilians they had encountered along their journeys. Many had traveled through the notorious Darién Gap en route to Tijuana, and some had lost loved ones along the way.

Empty beds in our empty shelter, once the border was closed and we had no more migrants to serve, under the poster “No One Stands Alone in Our Community,” in English & Spanish.

In fall 2024, Donald Trump and J.D. Vance began demonizing Haitians as pet-eaters, endangering the migrants I had sent to the Midwest. After the November election, and Trump’s vows to close the border immediately in his new term, I worried even more about the future. Fearful that migration rules would change, I signed up for as many shifts as I could as Inauguration Day approached. I scheduled airport shifts for the nights of January 18, January 20 (knowing clients would have had CBP One appointments that morning even if something catastrophic happened that afternoon), and January 26 (out of sheer hope). Though I mask indoors, on January 18 I started to feel sick during my shift, and told my favorite staff colleague that I thought I should go home. I said I hoped it wouldn’t be our last shift together. “What do you mean?” he asked optimistically. “The US needs immigrants. That can’t be, Alyssa! I’ll see you next week!”

But on January 20, immediately after being inaugurated, Trump declared the border “under attack,” portraying migrants as an “invasion.”[7] I was heartbroken seeing reports from Tijuana of families who had waited months or years for CBP One appointments, only to find the gates to safety slammed shut. I also worried about the impact of these polices on our staff. I checked the news frequently and texted my volunteer coordinator: Away from the cameras, were we still getting clients? As the days went on, the new reality became clear: all volunteer shifts were canceled. No asylum seekers were being allowed to enter.

On February 11, 2025, I received an email confirming my fears: federal funding had been pulled, and the shelter was closing. While JFS sought to help the 115 shelter and travel staffers find new jobs in or outside the agency, we planned a final party to celebrate – and mourn – what we had built and what it had meant to us. The gathering gave me an opportunity to talk with staff about what their work with migrants had meant – and surprisingly, to learn what we, the volunteers, had meant to them. Many (though not all) of us were White retirees. Given frequent negative discourses about immigrants, seeing the volunteers show up regularly to welcome migrants was consoling for individual staff members in a way I had not realized.

One colleague, whose parents immigrated from Mexico and who began working at the shelter in 2018, said: “Volunteers meant hope! The fact that you were all coming showed us that there were still good people” in the US and that “we still had allies.” Of her own motivation to help migrants, she added: “All we wanted to do was help people in need. They wanted a safe place to turn to and we promised them that.”

Another staffer, a recent college graduate, said working at the travel shelter had meant “Home! Coming here from a migrant family felt like helping another uncle or cousin. Getting to know them and learning from them was wonderful.” She loved that moms could have some respite from the stress of trying to cross while their children played with our toys. “Our work was beautiful,” she added. “I can’t express it in words to those who weren’t here.” Another longtime staffer explained that, before JFS, she had worked with migrants for the federal government – but “here,” she could be herself and give families all the help she wanted.

Obituaries for our shelter have been numerous. The San Diego Union Tribune reported: “The shelter provided services to more than 248,000 asylum seekers since [opening] in 2018, prioritizing … families, pregnant women, LGBTQ+ people and those with medical conditions.” The paper quoted JFS CEO Michael Hopkins praising shelter staff “for their tremendous, round-the-clock work to welcome with dignity every day…. We are proud of what we accomplished together.” Other news outlets reported that JFS was owed more than $22 million from the federal government for services it had already provided – money now being withheld – and that it would be pivoting to offering pro bono legal services to immigrants already here.[8]

Meanwhile, President Trump has declared prior entries through CBP One illegal, stripping legal migrants of their status overnight and targeting them for deportation. I had thought my passengers who got appointments in December 2024 and early January 2025 were the lucky ones – they would escape changes in border policies. But media reports have suggested they are even more vulnerable than those who entered illegally; they gave the government their names and their sponsors’ addresses. Some may be among those who were rounded up and sent to unthinkable conditions in Guantánamo or Panama.[9]

I am back to feeling heartbroken about US policy toward Haitians and other immigrants even while trying to raise consciousness on social media. On campus, I continue to try to unsilence Haitian history for my students, creating empathy with Haitians and helping students understand the impacts of US policies toward the country over 230 years. Using the anthology I published to help readers understand the historical factors that have harmed Haiti, along with other resources, I have to hold out hope that greater knowledge can spur change.[10] But I still think indignantly of the families so close and so far from us – who my colleagues and I would happily help, if only they could cross – and of those we did serve who face frightening new realities.

We welcomed with dignity, every day…. Until we couldn’t.

A sign “Stop Haitian Deportations,” with the Haitian flag, as it stood as part of the entrance to the shelter in 2023.

*This essay reflects the author’s own ideas and not necessarily those of JFSSD/SDRRN.

[1]Alex Dupuy, Haiti, from Revolutionary Slaves to Powerless Citizens: Essays on the Politics and Economics of Underdevelopment, 1804-2013 (Routledge, 2014); Paul Farmer, The Uses of Haiti, 3rd ed. (Common Courage Press, 2006); Nadève Ménard, “Helping Haiti - Helping Ourselves,” in Marin Munro, ed. Haiti Rising: Haitian History, Culture and the Earthquake of 2010 (Liverpool UP, 2010), 49-54; Mark Schuller, Humanitarian Aftershocks in Haiti (Rutgers UP, 2016).

[2]Alyssa Sepinwall, Translation and Introduction, “‘Beyond Help?’ Address by Raoul Peck, Conference on ‘Beyond Aid: From Charity to Solidarity,’ Frankfurt, Germany – Feb. 20, 2014,” in Toni Pressley-Sanon and Sophie Saint-Just, eds,. Raoul Peck: Power, Politics and the Cinematic Imagination (Lexington, 2015), 273 – 279.

[3]Emmanuela Douyon and Alyssa Sepinwall, “Earthquakes and Storms are Natural, but Haiti’s Disasters are Man-Made, Too,” Washington Post, Aug. 20, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2021/08/20/earthquakes-storms-are-natural-haitis-disasters-are-man-made-too/, cited in Haitian Bridge/Innovation Law Lab et al. v. Joseph Biden, Alejandro Mayorkas et al., Dec. 21, 2021, US District Court for the District of Columbia, https://int.nyt.com/data/documenttools/hba-v-biden/a8106eacd7c45afe/full.pdf, 13.

[4]Ayana Archie, “Joe Biden Says the COVID-19 Pandemic is Over. This is What the Data Tells Us,” NPR, Sept. 19, 2022, https://www.npr.org/2022/09/19/1123767437/joe-biden-covid-19-pandemic-over.

[5]See “Migrant Camp Cleared Between Border Fences Near San Ysidro,” KGTV, May 16, 2023, https://www.10news.com/news/local-news/migrant-camp-cleared-between-border-fences-near-san-ysidro.

[6]Kate Morrissey, “This San Diego Migrant Shelter Has Become an Integral Part of the Border,” San Diego Union-Tribune, Dec. 19, 2022, https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/2022/12/18/this-san-diego-migrant-shelter-has-become-an-integral-part-of-the-border-other-cities-are-taking-notice/.

[7]Executive Order, “Declaring a National Emergency at the Southern Border of the United States,” Jan. 20, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/declaring-a-national-emergency-at-the-southern-border-of-the-united-states/.

[8]Alex Riggins, “San Diego Migrant Shelter Hailed as National Model Will Shut Down,” San Diego Union Tribune, Feb. 17, 2025, https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/2025/02/15/san-diego-migrant-shelter-hailed-as-national-model-will-shut-down-with-100-plus-layoffs/; and Dani Miskell, “Jewish Family Service Pauses Migrant Shelter Services Until Further Notice,” KGTV, Feb. 19, 2025, https://www.10news.com/news/local-news/jewish-family-services-pause-migrant-shelter-services-until-further-notice.

[9]Of a man sent to Guantanamo after using CBP One, see Julie Turkewitz and Hamed Aleaziz, “Family of Venezuelan Migrant Sent to Guantánamo: ‘My Brother Is Not a Criminal,’” New York Times, Feb. 11, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/02/11/world/americas/luis-castillo-venezuela-migrant-guantanamo-bay-trump.html; and Julie Turkewitz, Hamed Aleaziz, Farnaz Fassihi and Annie Correal, “As Trump ‘Exports’ Deportees, Hundreds Are Trapped in Panama Hotel,” New York Times, Feb. 18, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/02/18/world/americas/trump-migrant-deportation-panama.html

[10]Sepinwall, Haitian History: New Perspectives (Routledge, 2012).