Learning How to Braid Knowledge through Visual Media

By Sarah Jacqz, Erica Wolencheck, and Ryan Rybka

3.1 Sarah Jacqz

In my last year of undergraduate studies, I took Contemporary Native American Issues with Dr. Sonya Atalay. As part of a semester of reading and listening to visiting Indigenous scholars, writing, mapmaking, and more, our central project of creating graphic novels was a powerful way to learn a transformed approach to knowledge sharing and creation, through practice.

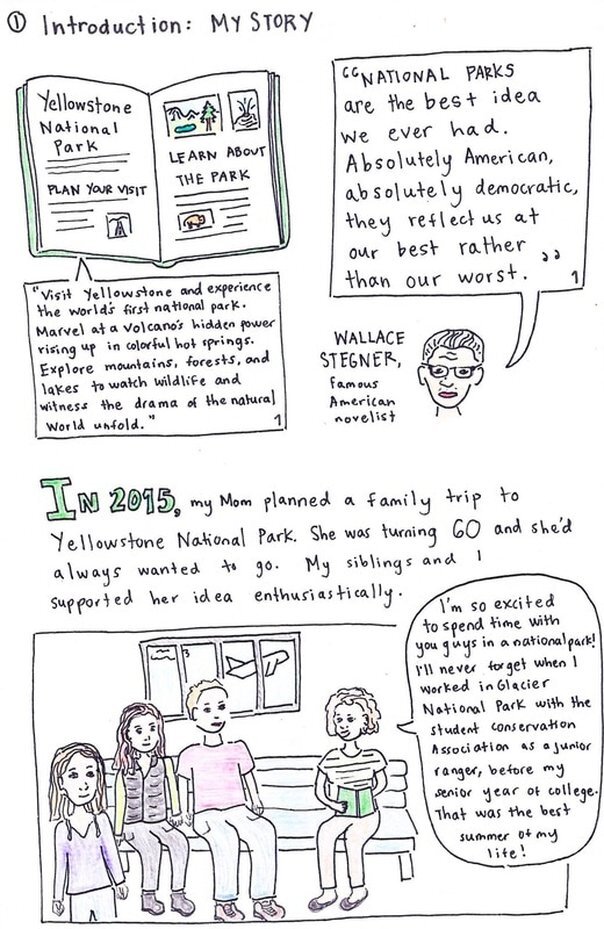

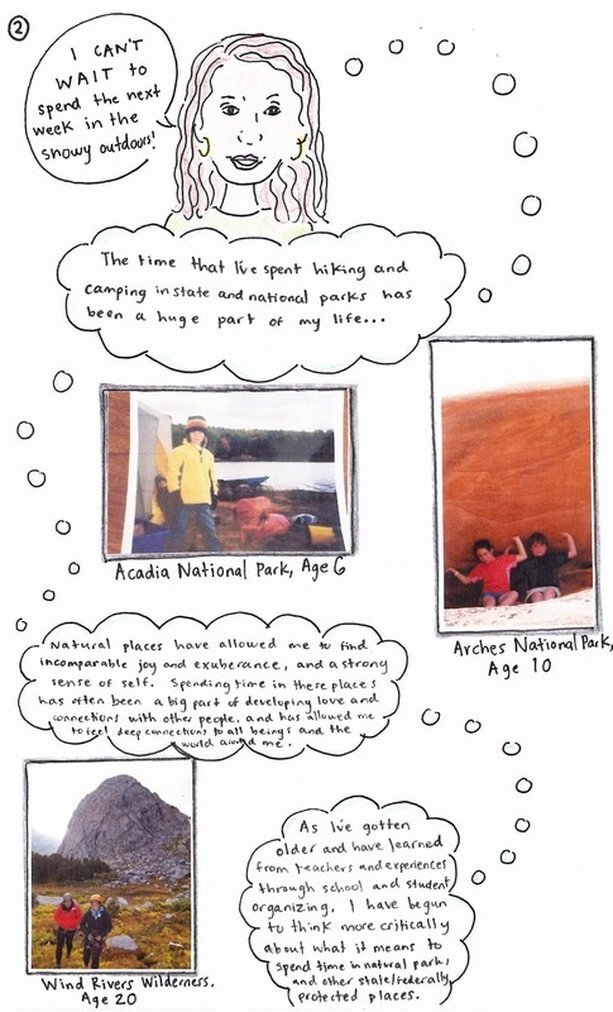

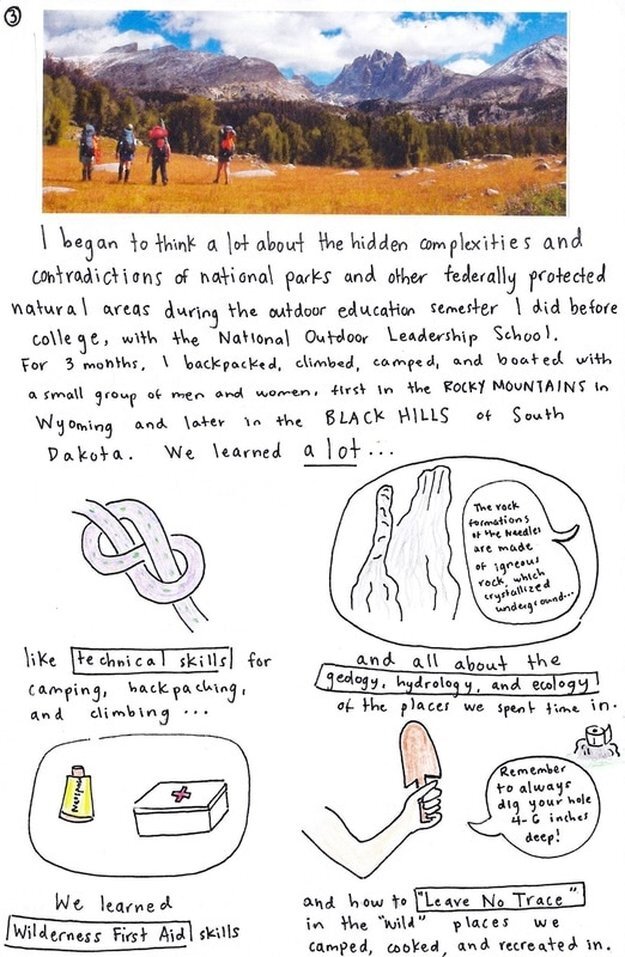

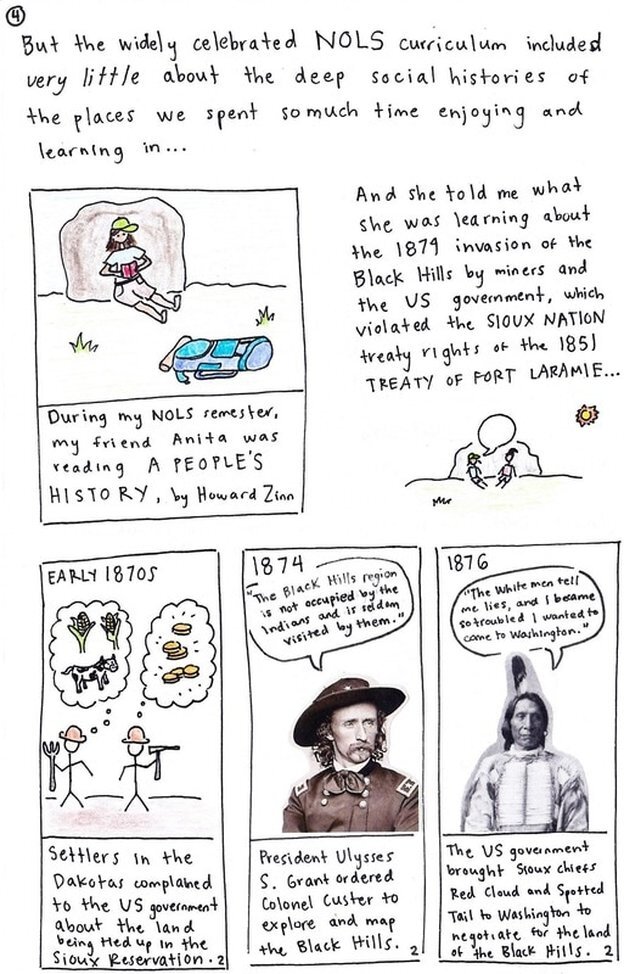

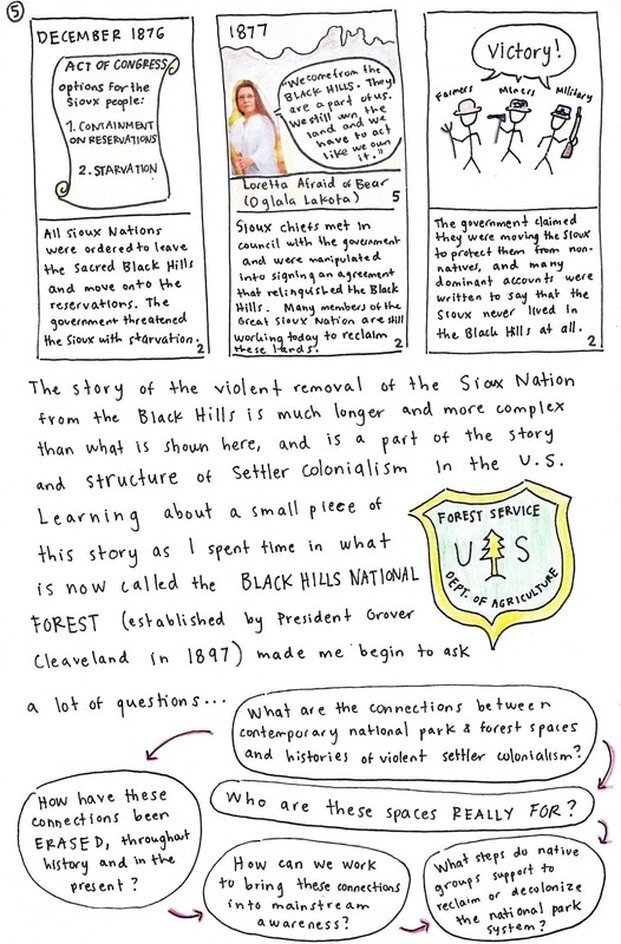

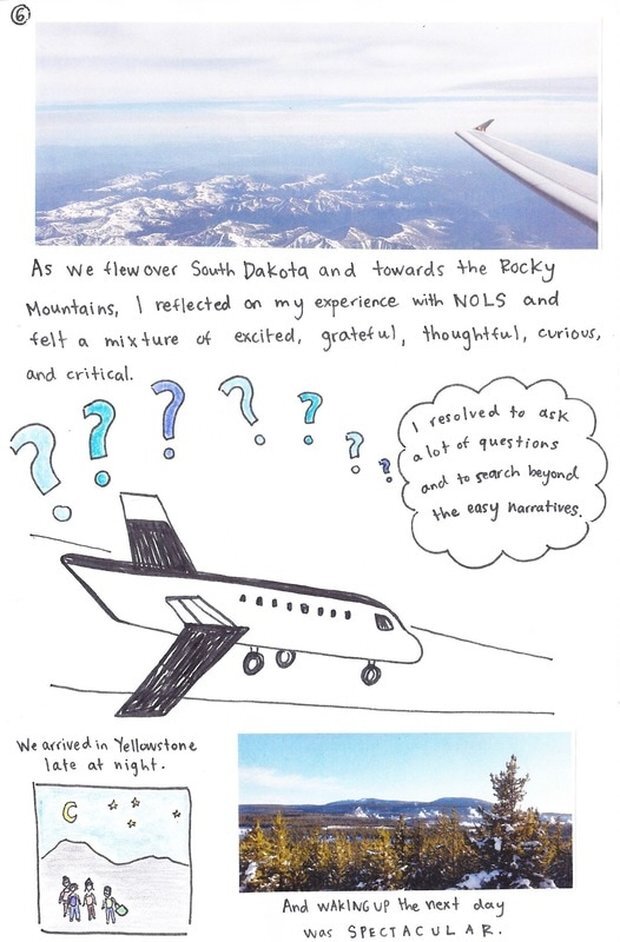

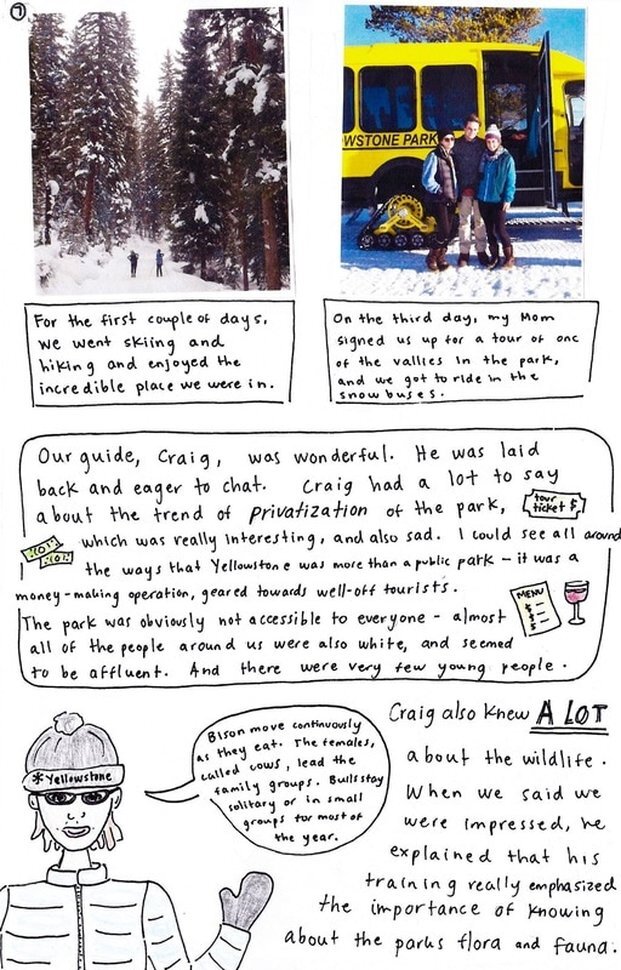

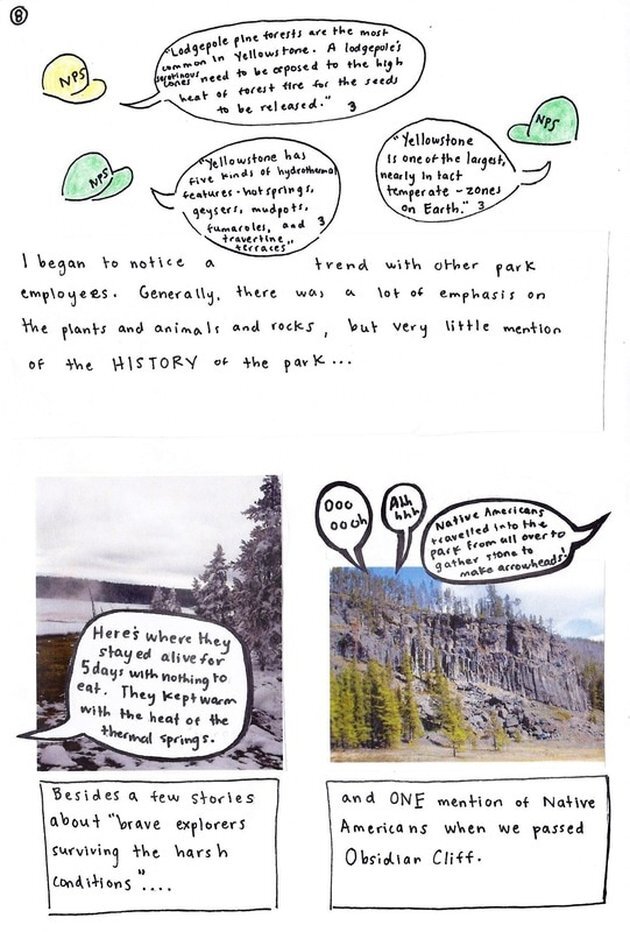

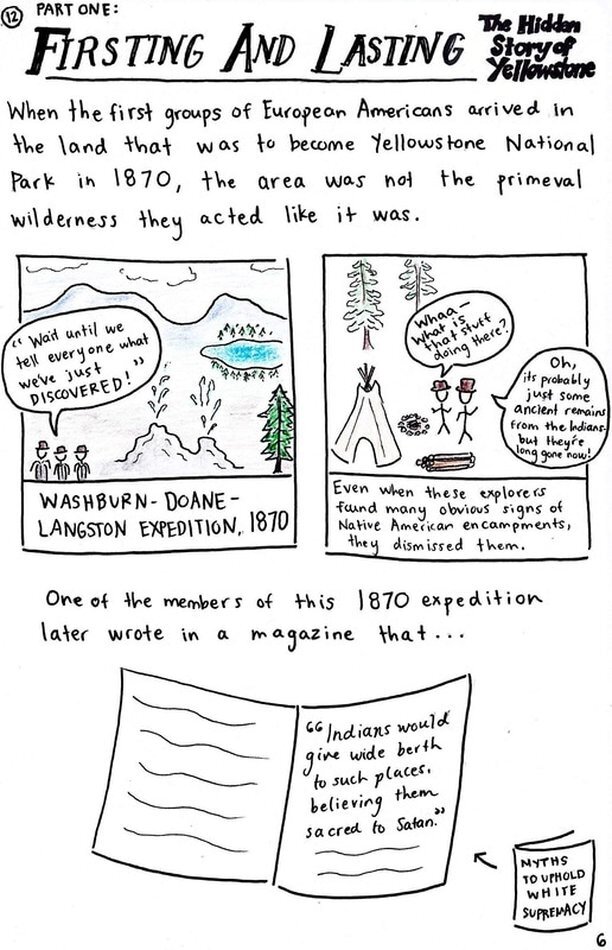

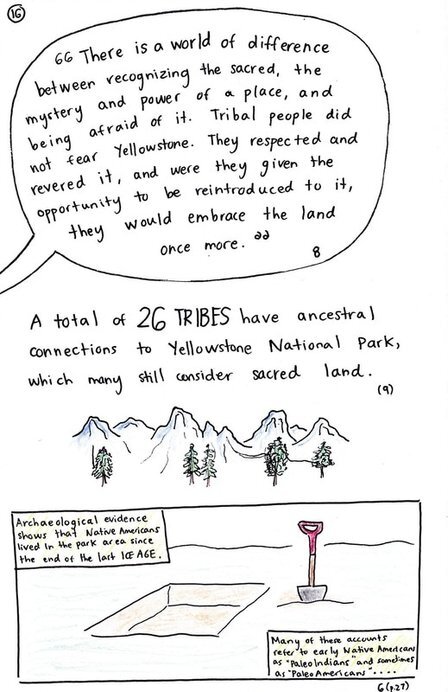

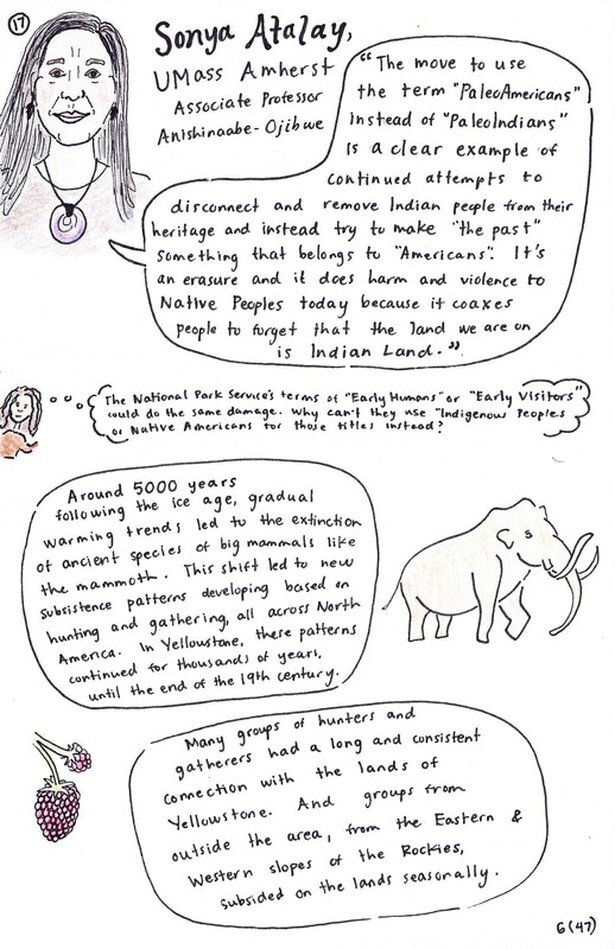

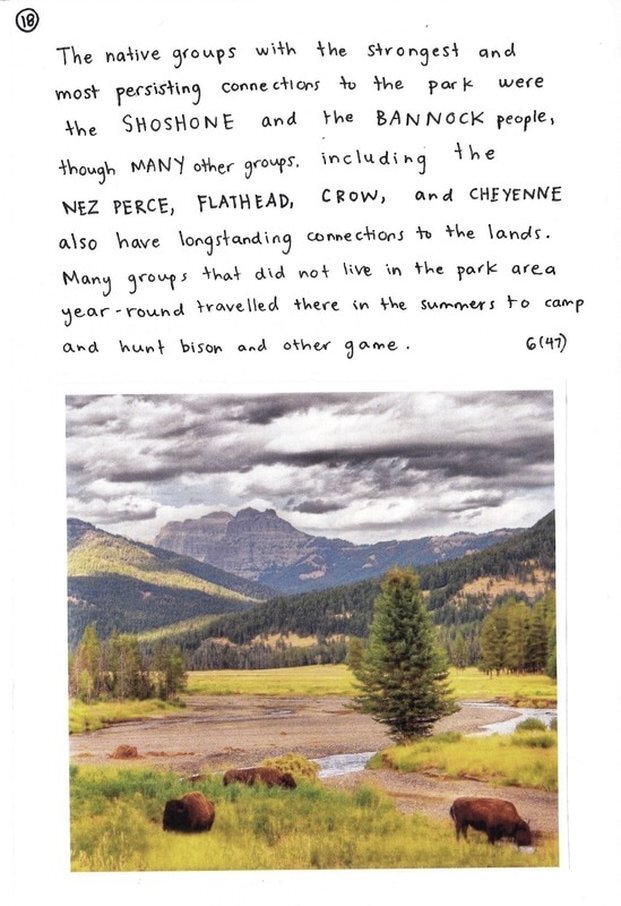

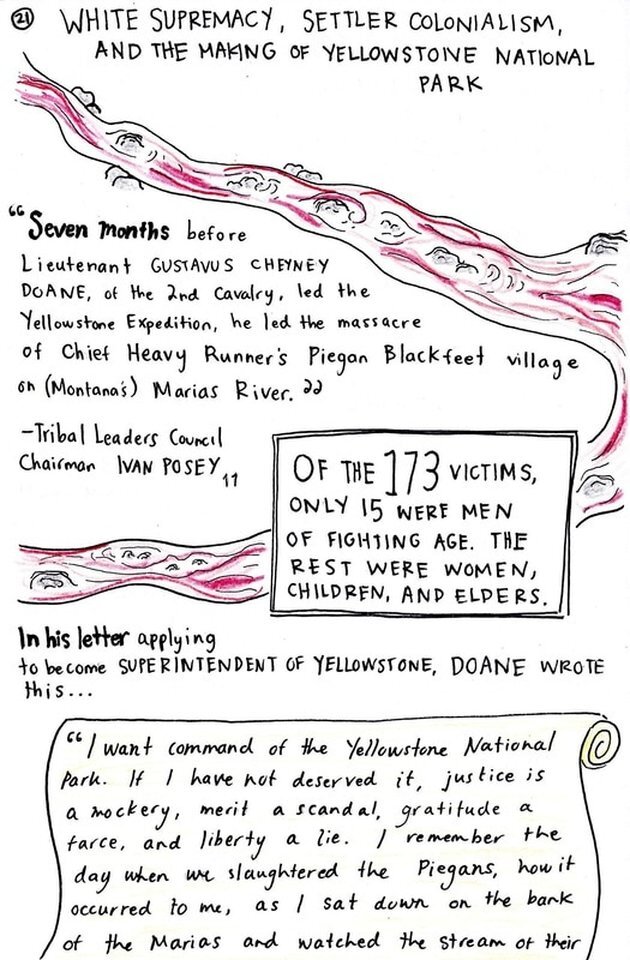

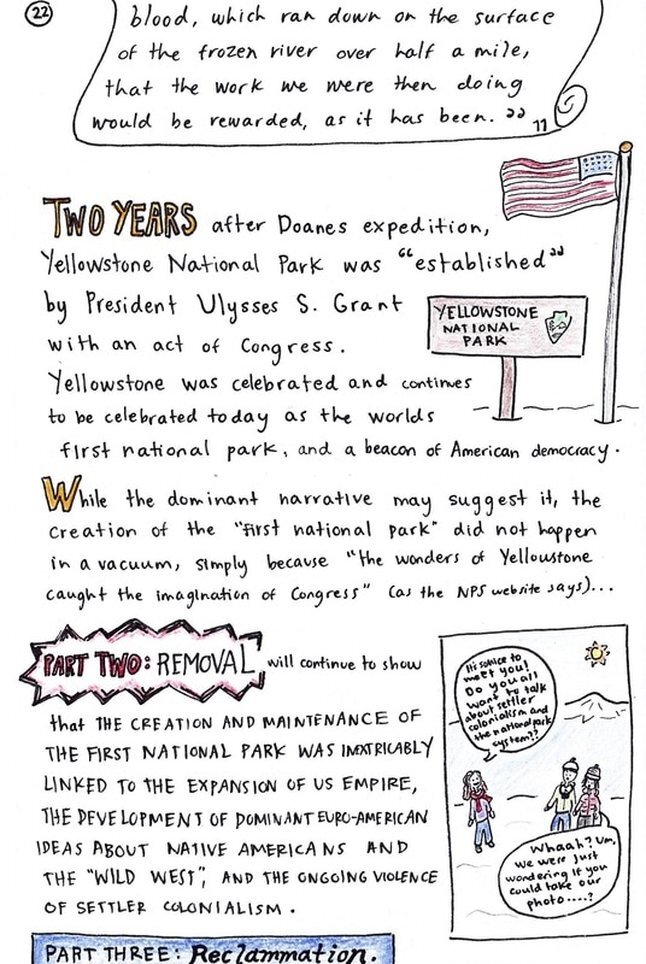

My graphic novel (below and online) was about national parks, and specifically the ancestral lands of the Shoshone, Bannock, Nez Perce, and many more groups, which is now called Yellowstone National Park. The memory of a previous family trip to this place inspired me to critically explore my own experience as a white person with class privilege traveling in national parks to understand how structures of white supremacy dominate and erase the Indigenous history and present relation with these lands and to uncover some of the truths about Yellowstone that had been colonized. My graphic novel process encouraged me to embrace and learn through an awareness of my own position in the enormous web of life and knowledge. Learning from Dr. Atalay and many Indigenous scholars in this class emphasized a kind of knowledge production rooted in connection: the connections between all human and nonhuman life, and the connections spanning time and generations.

As a white woman, I know that the violences of settler colonialism have deeply damaged my own relations to Indigenous peoples and the land. Only by starting with deep awareness of where we each stand in this web can we can begin to repair the damaged connections. Visual storytelling with graphic novels or other media, which are naturally vulnerable, story-based, creative, and forgiving, is a powerful way to grapple with and share understanding of these connections. To illuminate one’s place in this web through visual media allows us to disrupt the dominant settler-colonial ideologies of learning: that we can be objective and unbiased scholars or that there is such thing as one universal truth, which destroys and replaces all others.

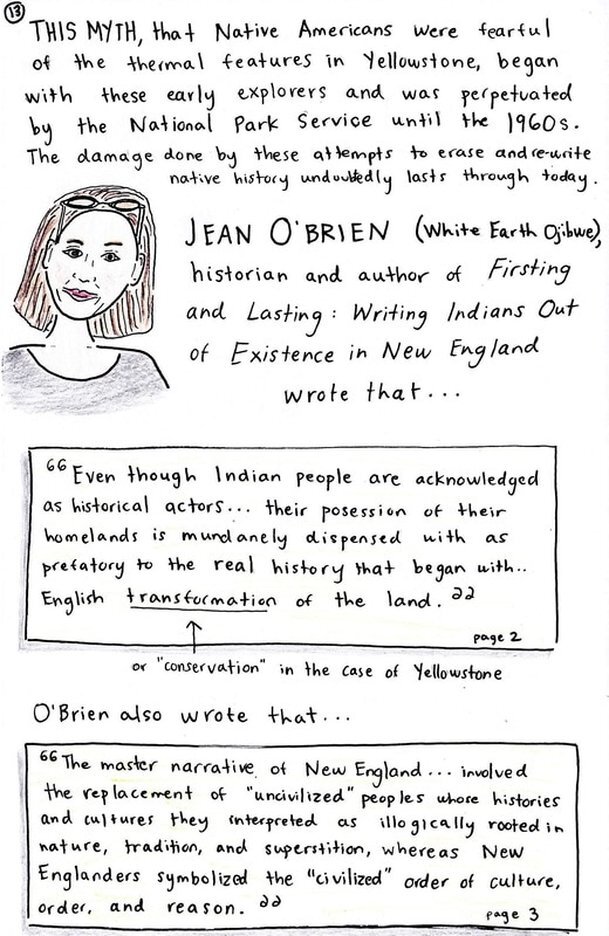

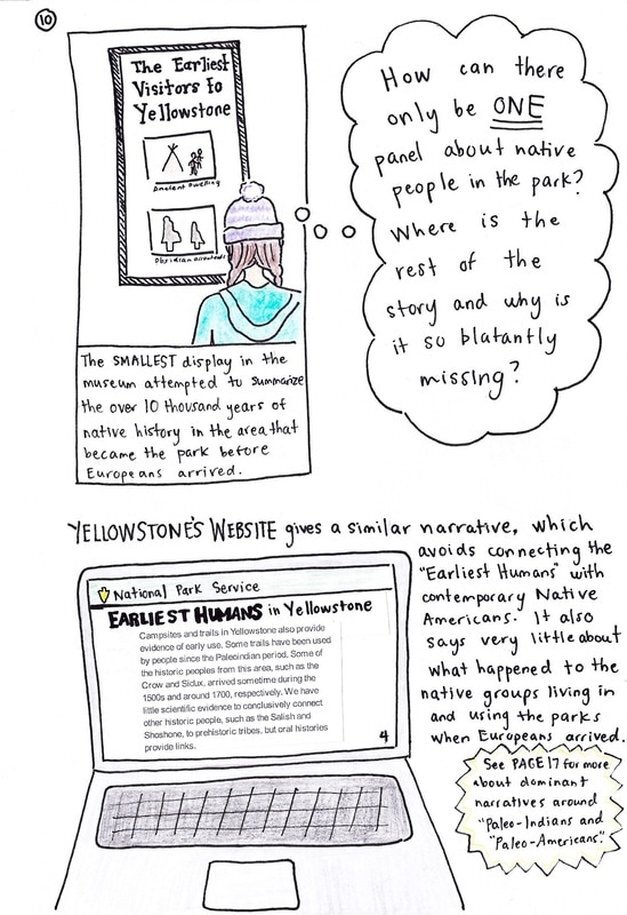

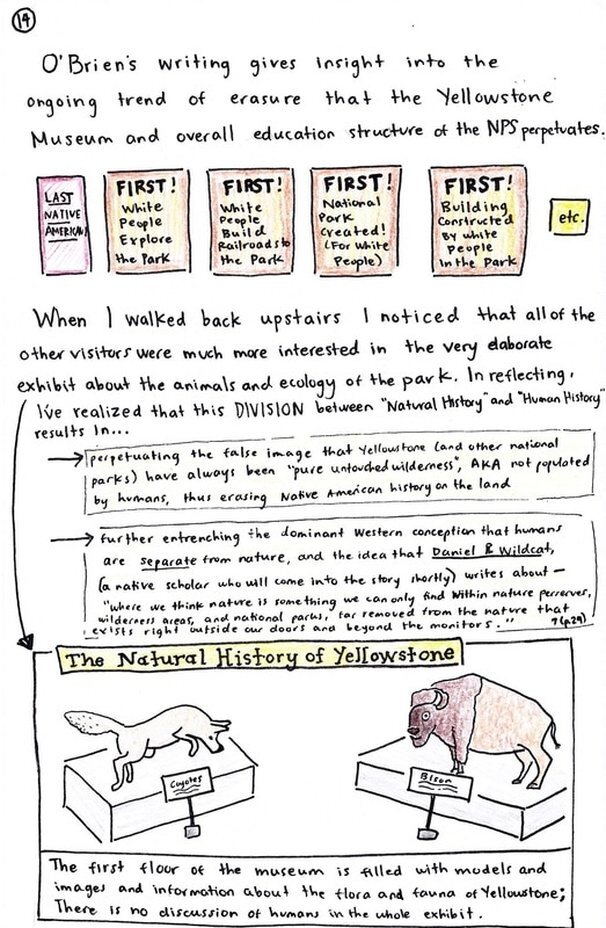

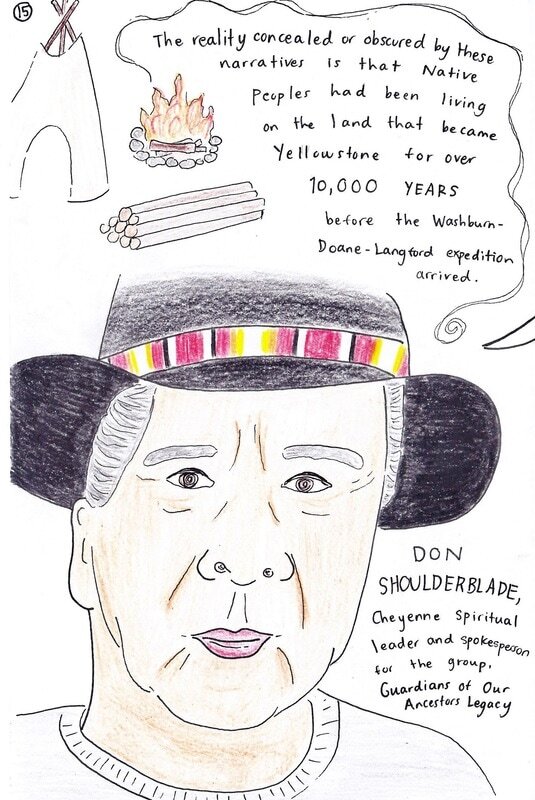

I used firsthand storytelling with characters, speech, and thought bubbles to show my experience of visiting the park and being told a story by tour guides and the museum: of Yellowstone National Park as a success story of white man’s discovery and “conservation,” a story which included only very brief and superficial references to Native people. In my graphic novel, I share my journey of seeking out a more truthful history of Indigenous peoples’ relationship to this place. I use illustrations and direct quotes to bring the perspective of several Indigenous voices, as well as to expose the colonial violence that created Yellowstone, bringing honesty and emotion to a painful truth that has been so carefully covered up.

The dynamic process of reflection, listening, research, and visual storytelling for my graphic novel allowed me to engage in a decolonized form of knowledge and to begin to feel repair and healing in my place in the web of connections.

Sources

1- “Yellowstone National Park (U.S. National Park Service.” National Parks Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Web. 25 Mar. 2017.

2- Ojibwa. “The Theft of the Black Hills.” Native American Netroots. 9 Dec. 2011. Web. 25 Mar. 2017.

3- “Nature.” National Parks Service. Department of the Interior. Web. 25 Mar. 2017.

4- “History and Culture.” National Parks Service. Department of the Interior. Web. 25 Mar. 2017.

5- “The Roosevelt Arch at Yellowstone’s North Entrance.” Yellowstone Park. 15 July 2016. Web. 25 Mar. 2017.

6- Spence, Mark David. Dispossessing the Wilderness: Indian Removal and the Making of the National Parks. Oxford: Oxford UP. 2000. Print.

7- Wildcat, Daniel R. Red Alert!: Saving the Planet with Indigenous Knowledge. Golden, CO: Fulcrum, 2009. Print.

8- Landry, Alysa. “Native History: Yellowstone National Park Created on Sacred Land.” Indian Country Media network. 01 Mar. 2017. Web. 25 Mar 2017.

9- R Bear Stands Last. “Yellowstone National Park: A Glimpse Behind the Myth.” Guardians of Our Ancestors Legacy. 2010. Web. 25 Mar. 2017.

10- Ojibwa. “National Parks and American Indians: Yellowstone.” Native American Netroots. 22 Sept. 2010. Web. 25 Mar. 2017.

11- Wyofile, Augus Thuermer Jr. “Don’t Honor Proponents of Genocide! Tribes Want Yellowstone Names Changed.” Indian Country Media nEtwork. 14 Jan. 2015. Web. 25 Mar. 2017.

12- O’Brien, Jean. Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians Out of Existence in New England. UM Press, 2010. Print.

3.2 Erica Wolencheck. What Does It Look Like? Conveying Archaeological Information Visually

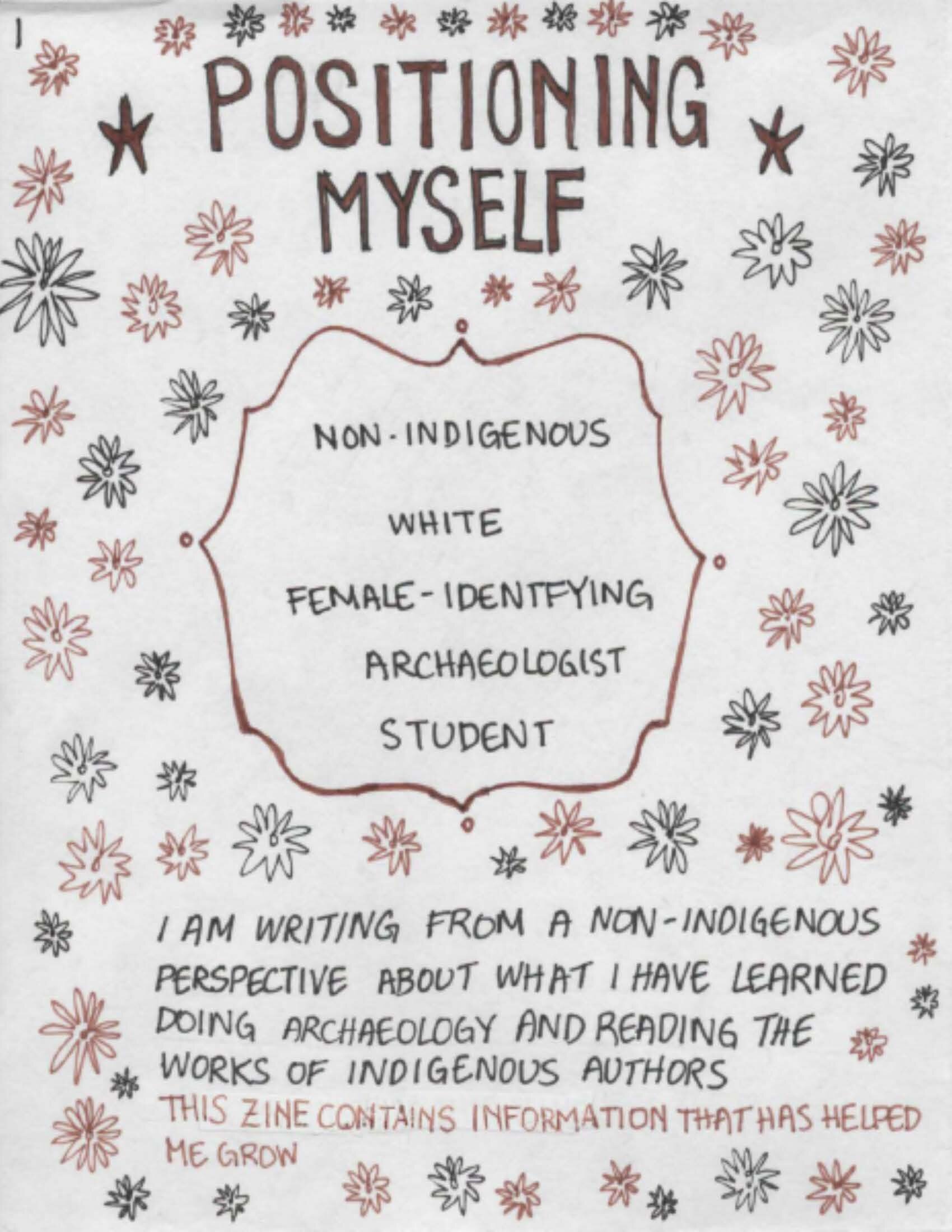

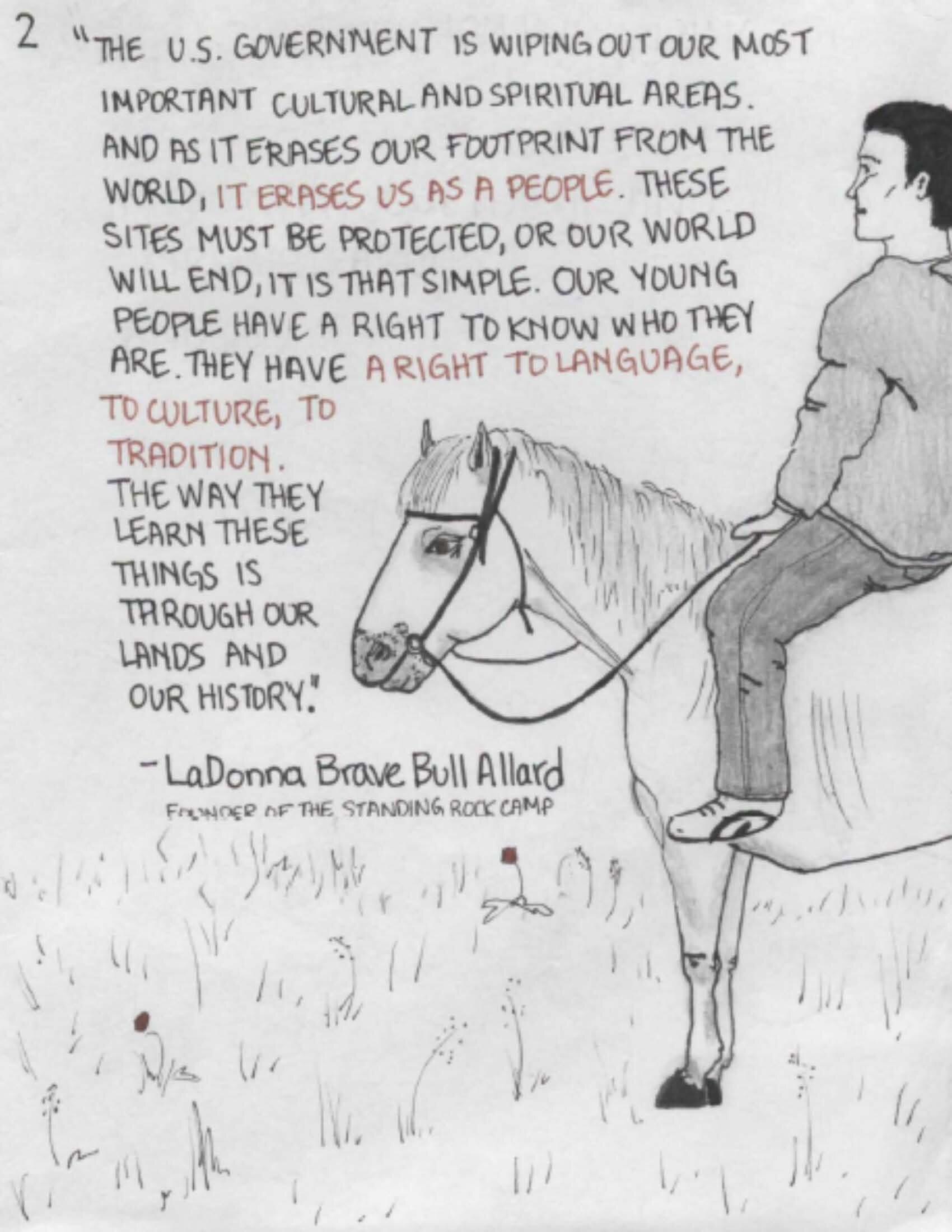

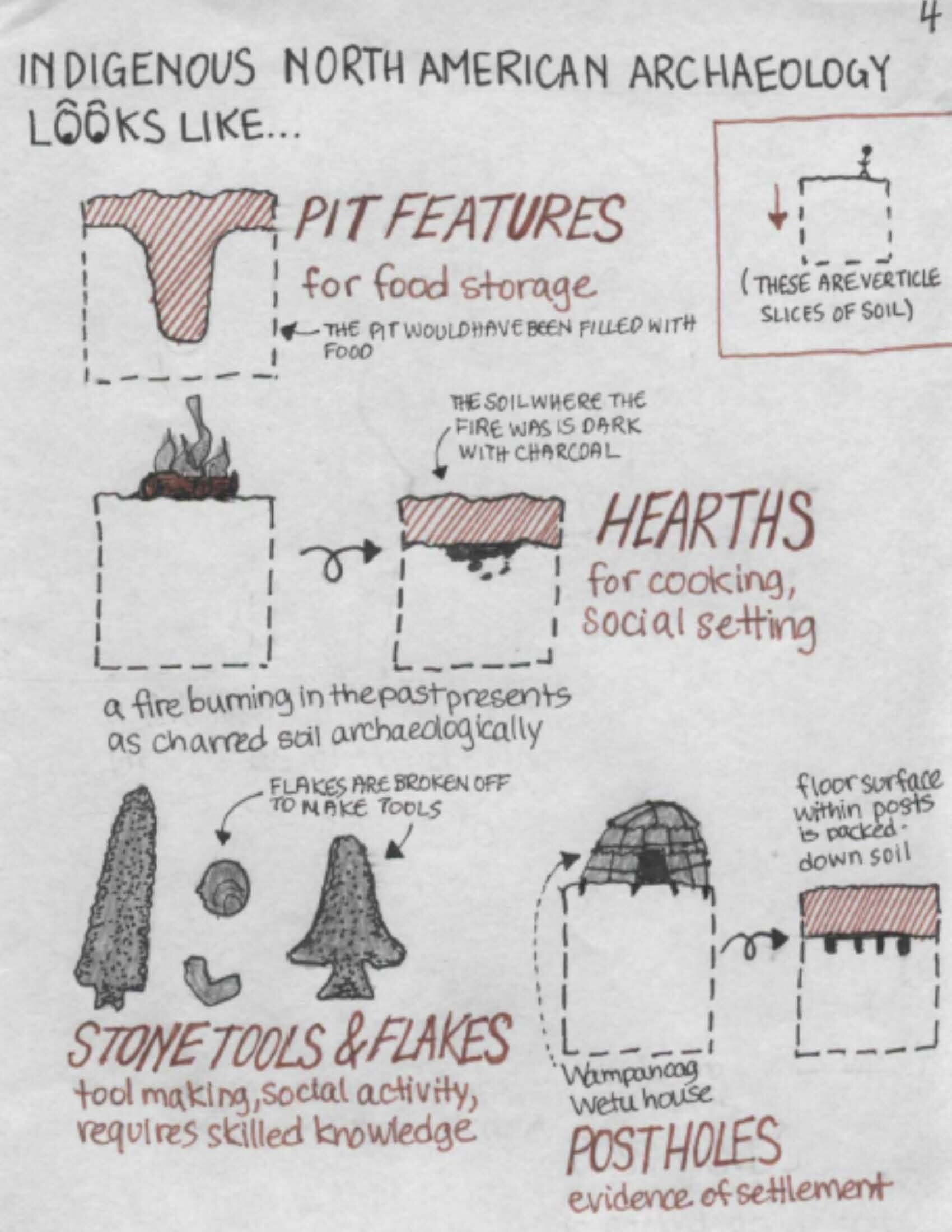

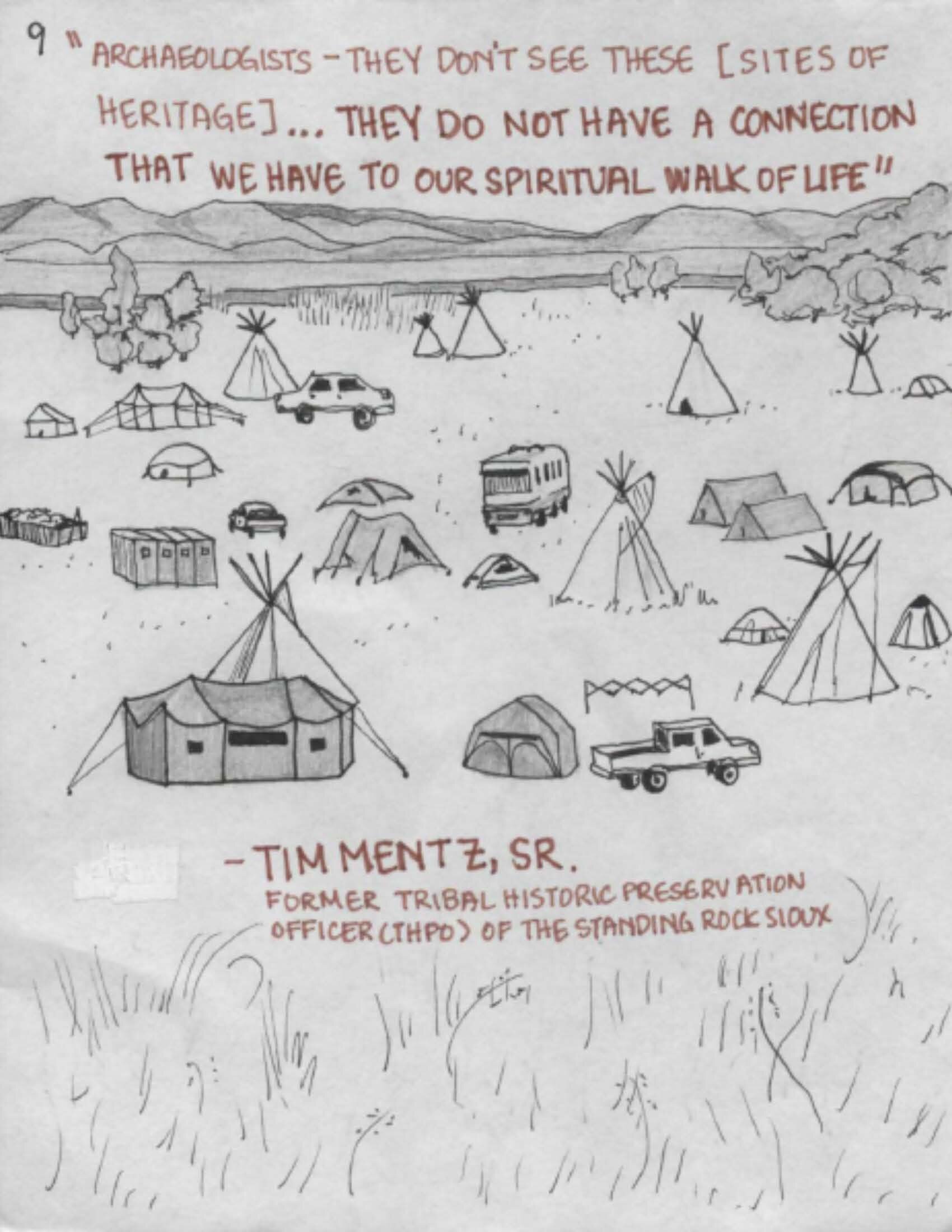

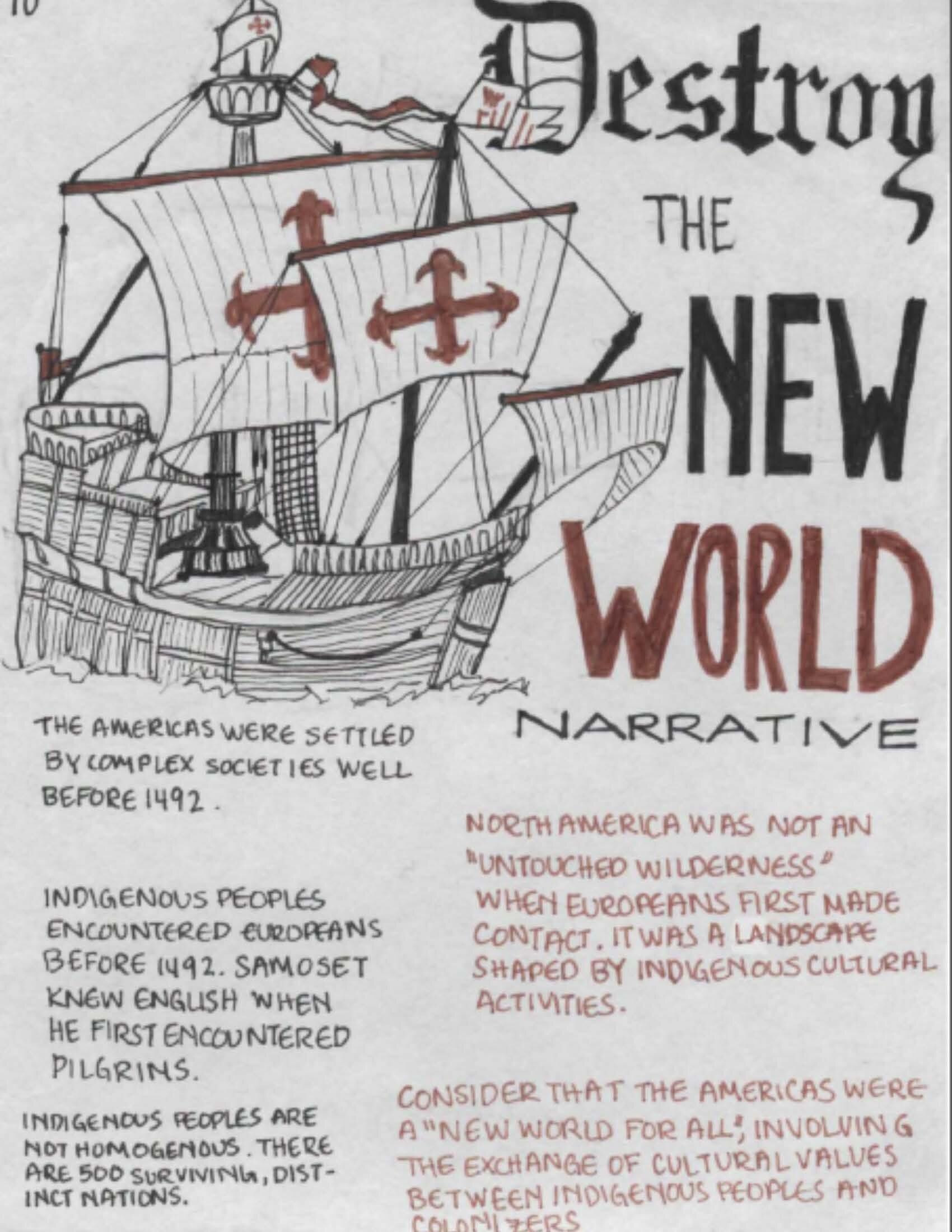

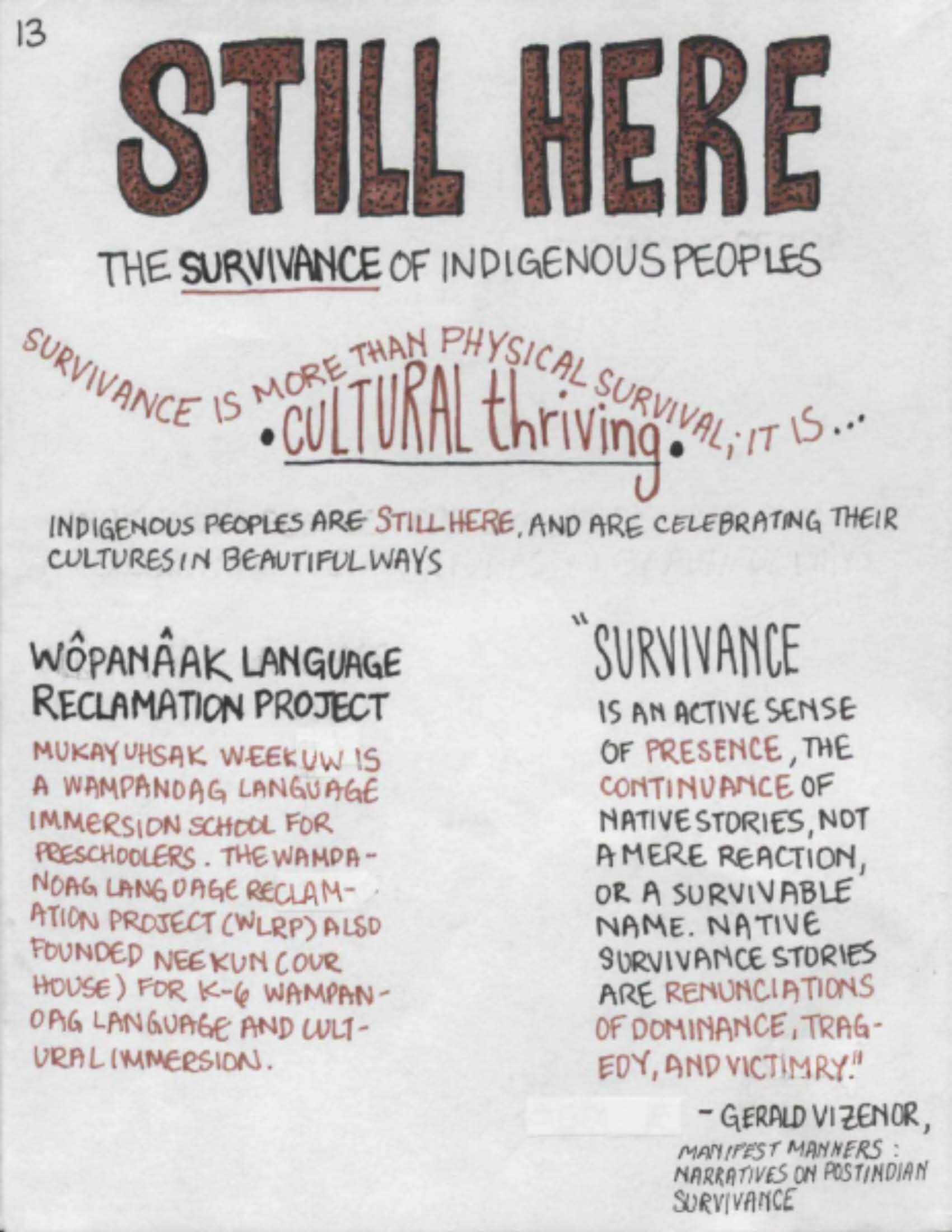

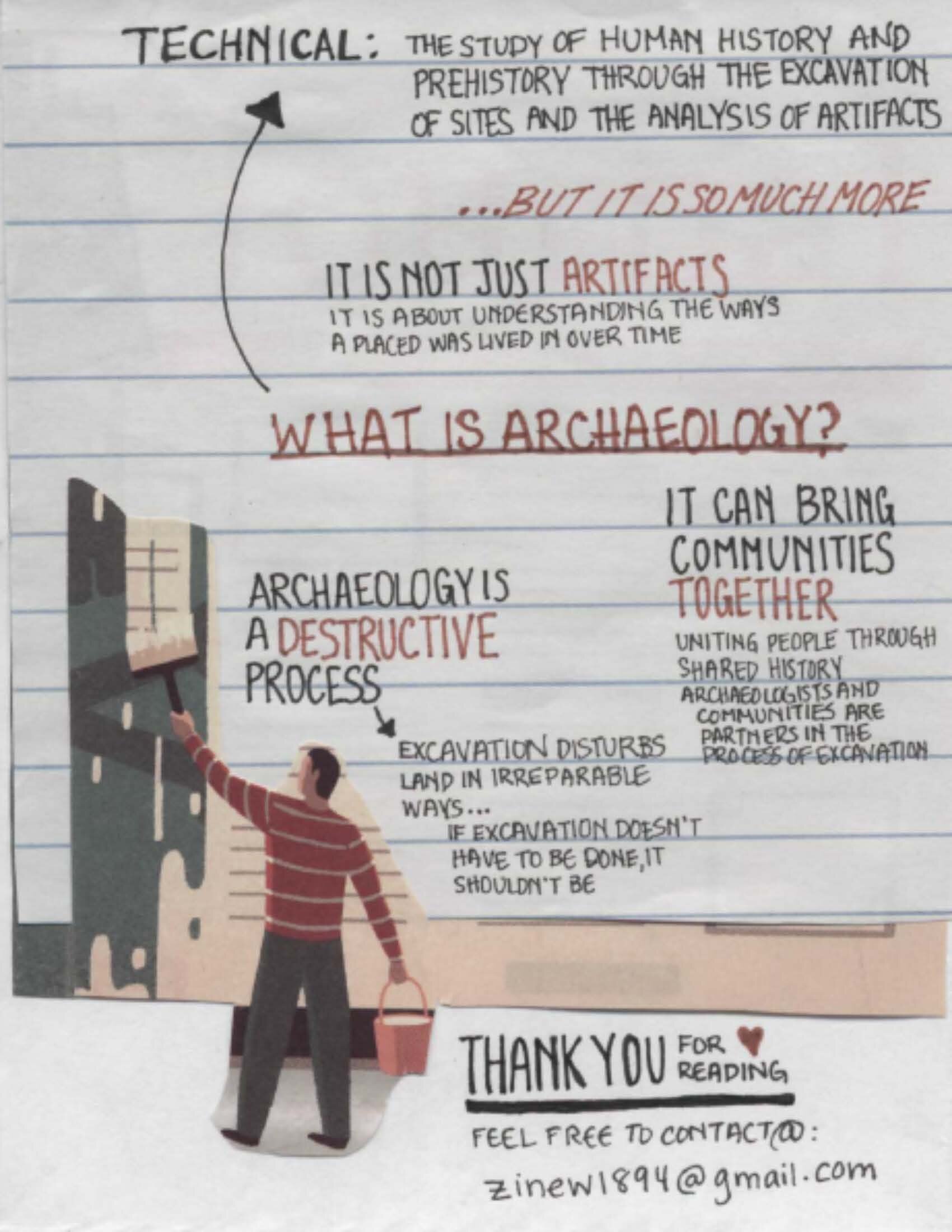

Working within the theme of visually conveying information, I created a “zine,” a small pamphlet composed of visuals and texts that can be easily reproduced. The zine covered the topics of North American archaeology, legislation, and Native histories in the Connecticut River Valley region. This zine, created in conjunction with my senior thesis at UMass Amherst under the direction of Dr. Sonya Atalay, was intended for an audience of non-Indigenous students. Titled “What Does It Look Like?: North American Archaeology, Human Rights, and the Standing Rock Reservation,” the zine focuses on seeing these subject matters. I made this zine during the height of the Standing Rock movement, inspired and guided by strong Indigenous voices and the relevance of my field of study, archaeology, in matters of land, identity, belonging, and human rights.

My positionality is key to the ways I conduct and communicate my research. I am a non-Indigenous white woman working as an archaeological field technician in cultural resource management. My engagement with Native histories and materialities is grounded in this work. I make sure to recognize that fully and approach my research with a mindfulness of and respect for Indigenous cultures and materialities.

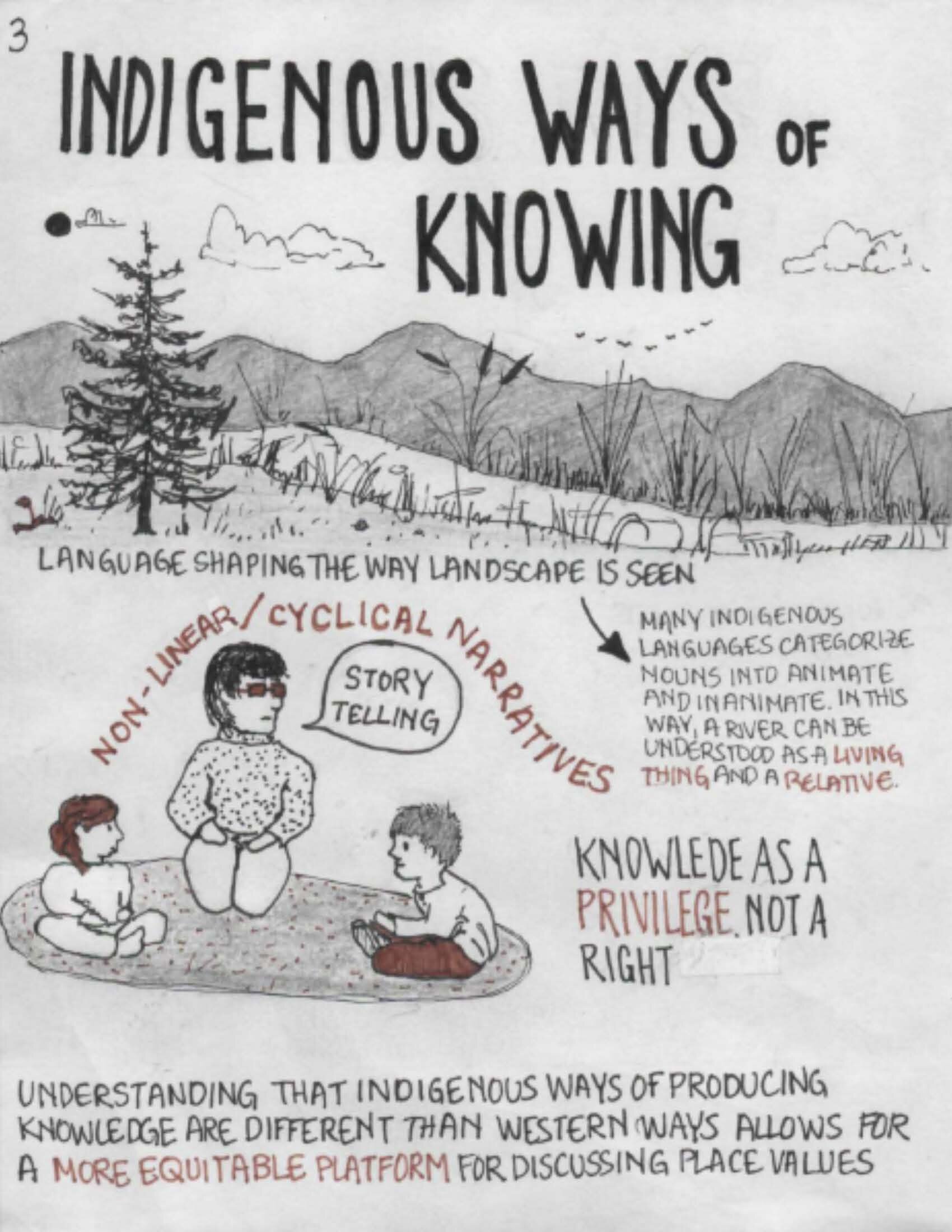

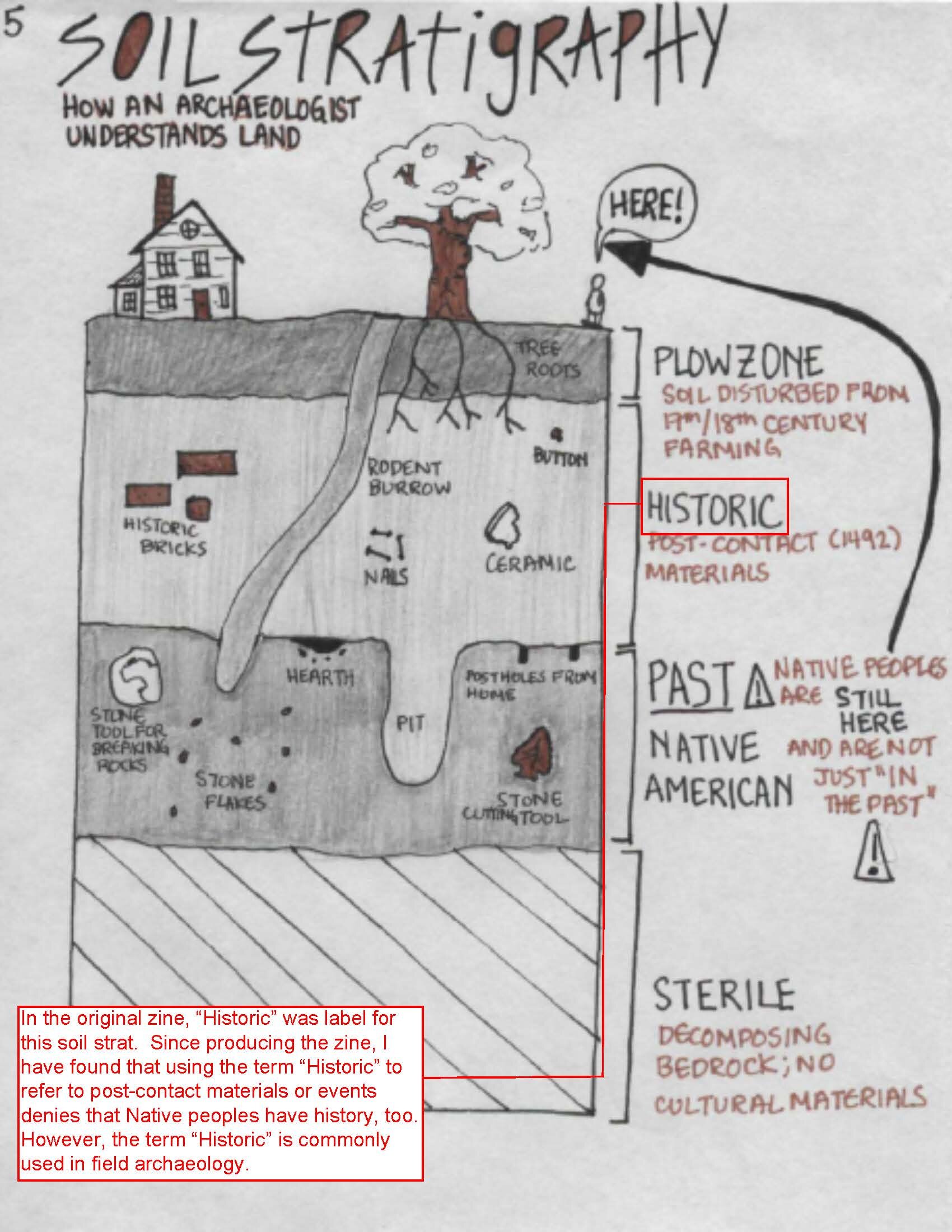

Archaeology is a field that utilizes the senses. During an excavation, a large part of how I understand landscape is visually, through soil changes, relative dating, and physical objects. Visual media communicates what I am seeing and conveys it in a way that is accessible to laypeople. This medium is not only cohesive with the ways I understand CRM, but also aligns with Indigenous ways of knowing.

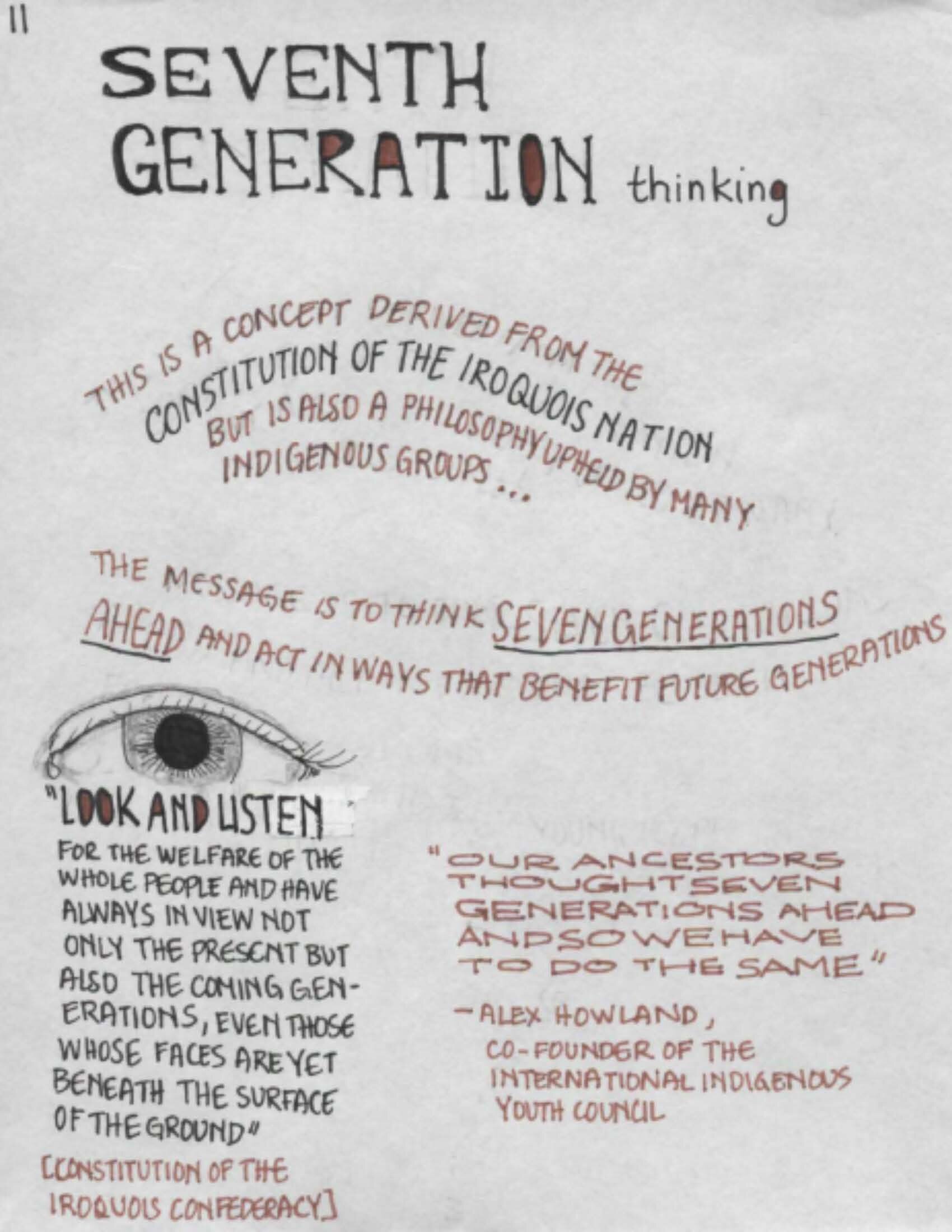

My zine presents a brief introduction to Indigenous pedagogy. I specifically cite the privileging versus the expectation of knowledge, nonlinear narratives, and seven-generation thinking as examples. I am careful to make text blocks short but information-dense. I make sure to also include Indigenous voices and provide sources of Indigenous literature that helped inform my understanding. Producing this zine better informed my senior thesis, providing a different means for comprehending outside of a linear construction.

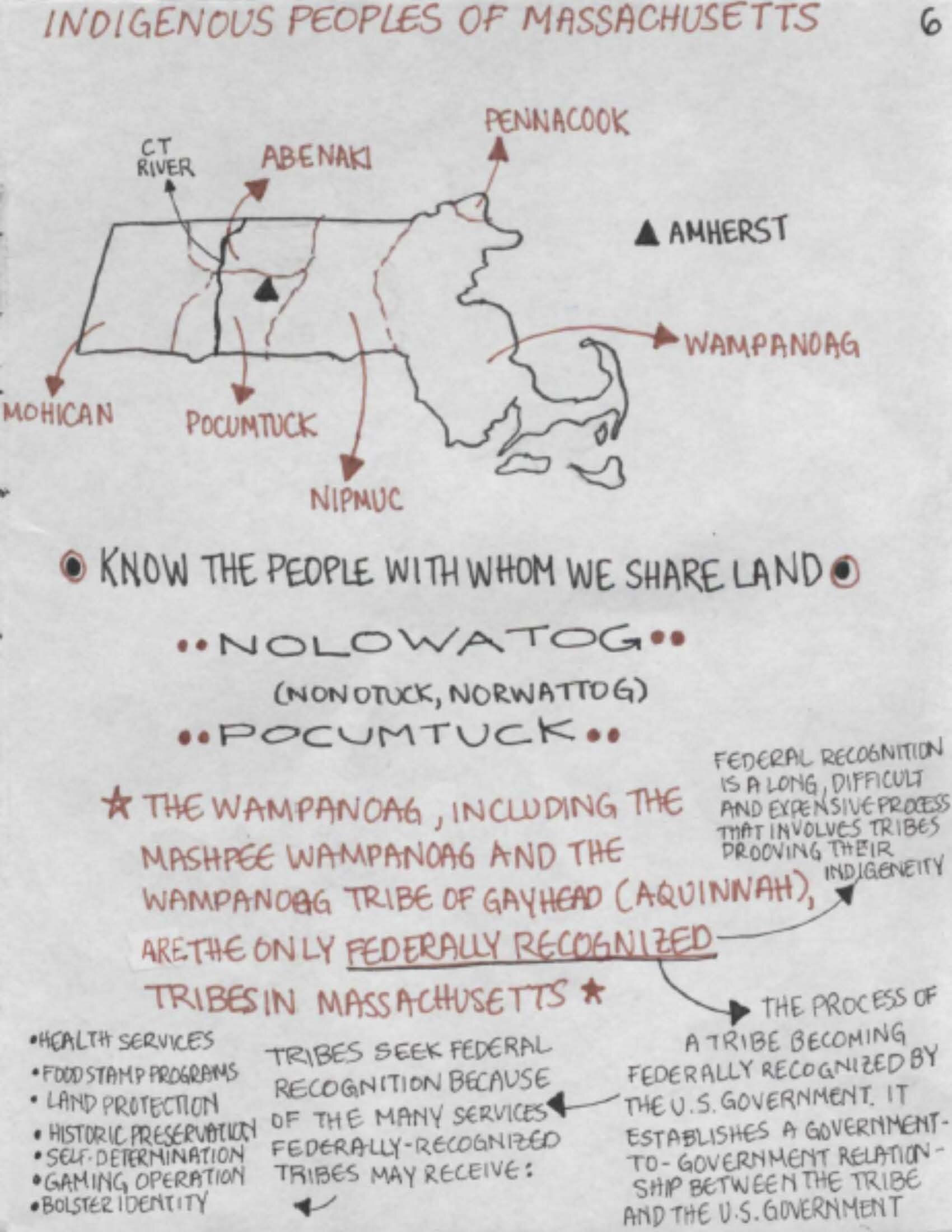

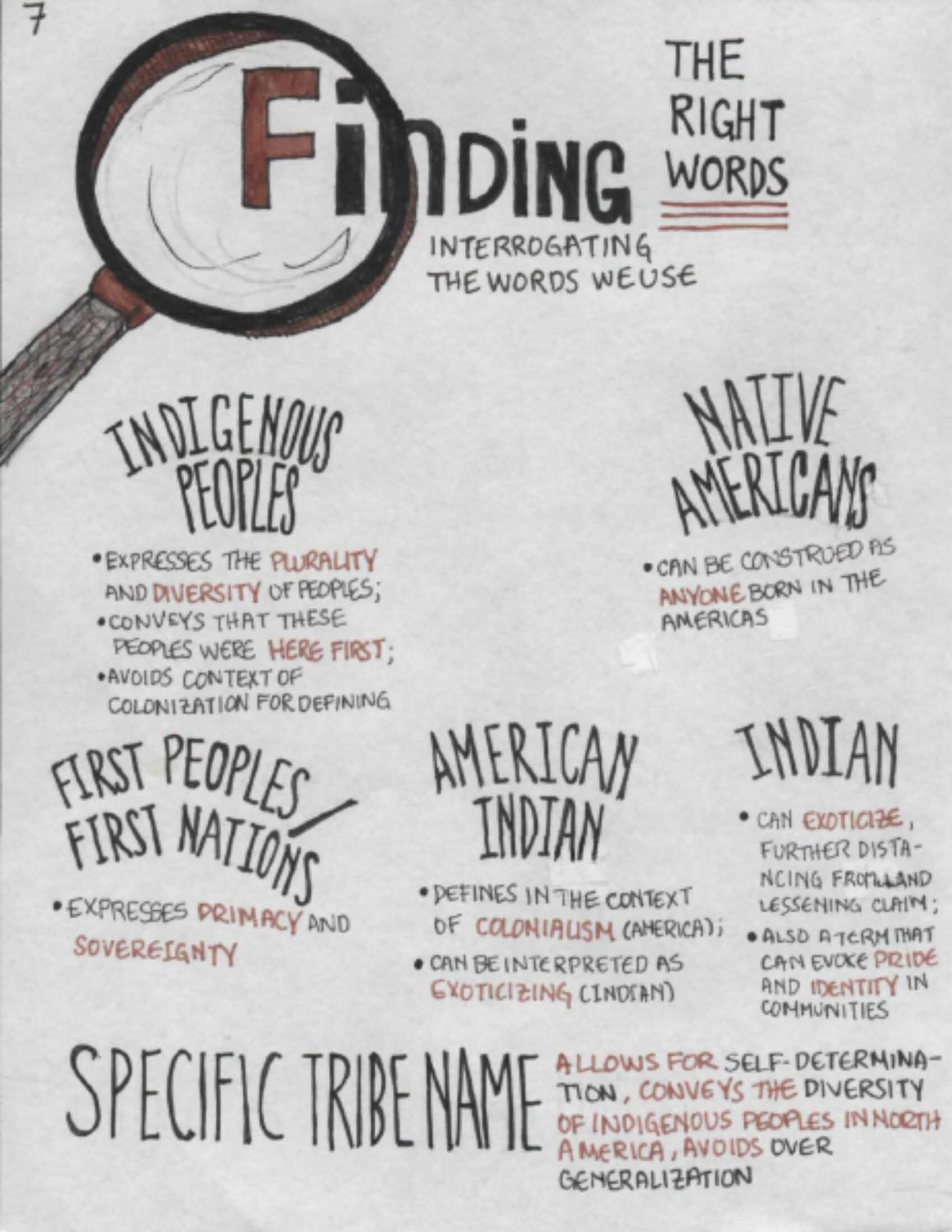

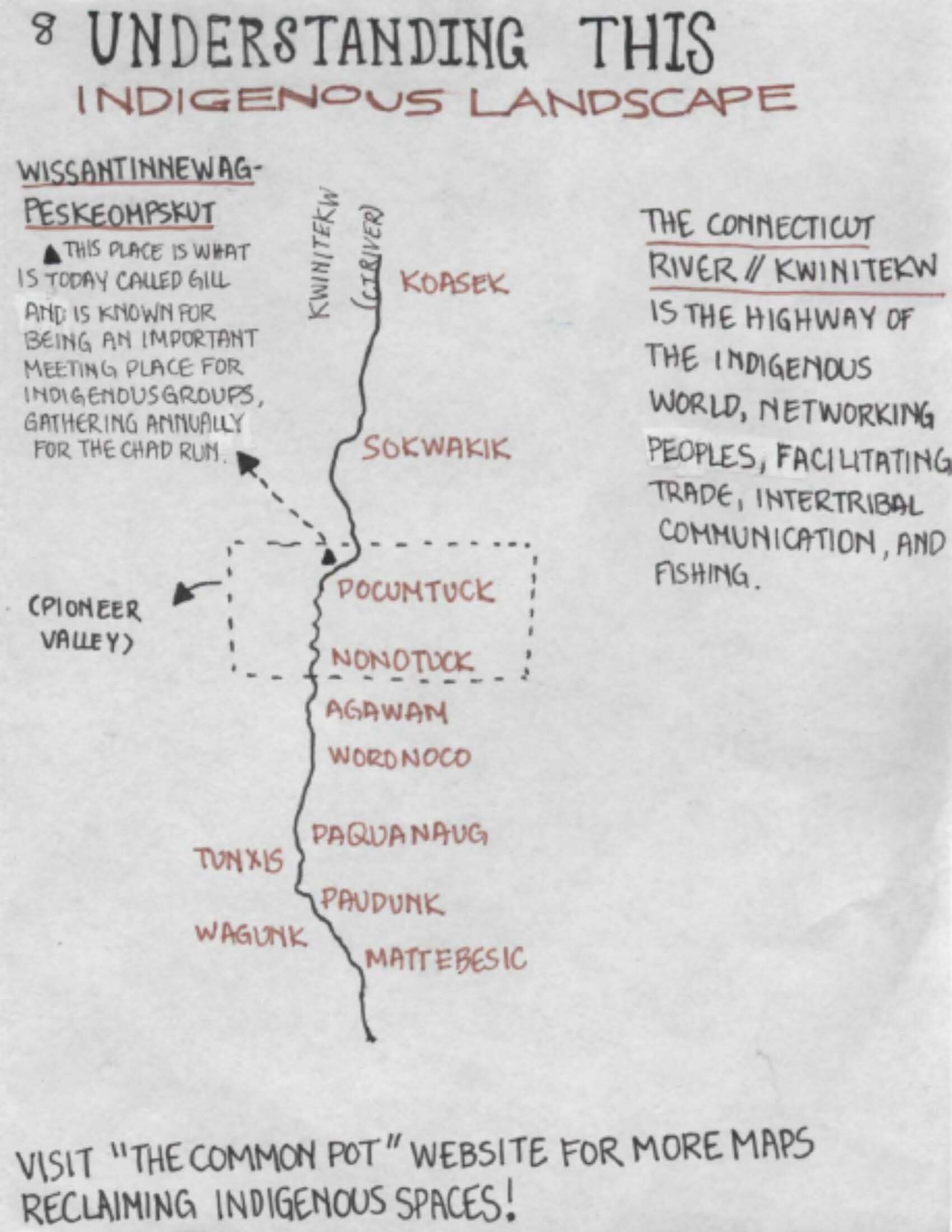

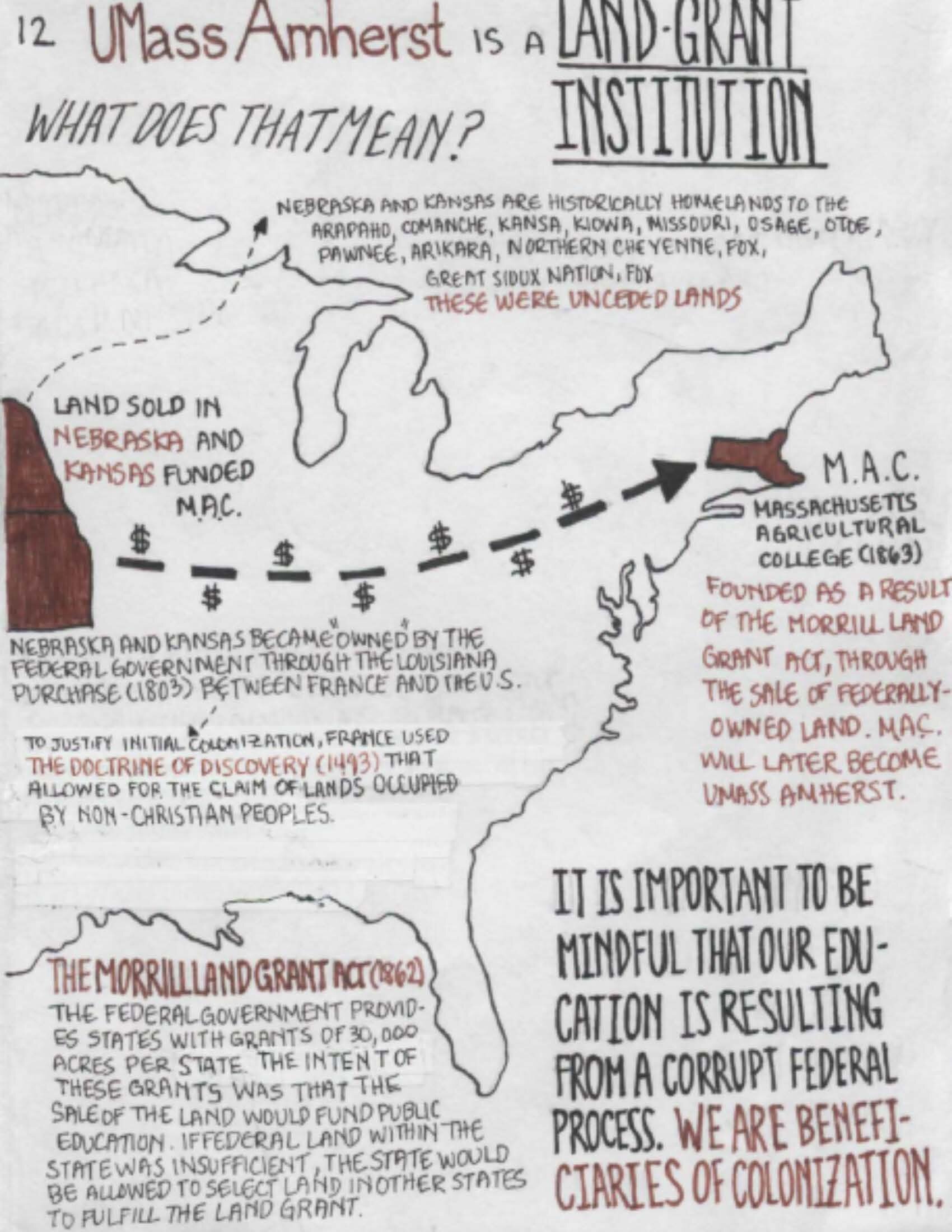

The intent of this zine was to inform non-Indigenous students about the land on which we learn and live in Amherst, Massachusetts, which are Pocumtuck and Nolowatog lands, and show what the study of this land looks like. I used maps to make clear the process of federal recognition and to communicate the dissonant histories of UMass Amherst as a land-grant institution. Using landscape to teach was a method of disrupting the Western canon of knowledge production. Learning how important the Connecticut River is and was to Indigenous lifeways refocused my knowledge of Indigenous histories from objects to land. Meaning became infused within the landscape and allowed for a more holistic understanding. This was an important shift in my awareness and my archaeological perspective. The feedback I received from the intended audience was positive, with general appreciation and surprise from the content, especially information relating to the Morrill Land Grant. The creation of and response to this zine was rewarding, encouraging myself and others to inquire further into Native histories and pedagogies.

3.3 Ryan Rybka. Water Protectors

Conflicts over access to and study of the archaeological record have cut deep into the field of anthropology through the turbulent times that birthed NAGPRA, the theoretical and methodological implications of processualism and postprocessualism, and the development of decolonizing methodologies, such as Indigenous archaeology. Conflicts over the openness of the archaeological record arguably demarcate the fuzzy boundary that exists between the understanding of an “open” past and “open” land—two realms that promise acquisition of resources and the generation of profit from the exploitation of land.

What Next? Braiding Desire-Based Research from Plymouth to the Dakota Access Pipeline, is a graphic novel that serves as a personal archaeological reflection. It begins with New England historical archaeology and transitions into how archaeology can be a powerful means to engage with contemporary contestations surrounding resource extraction on Indigenous land—an issue of national and global significance. The narrative structure consists of four fundamental themes.

FOUR FUNDAMENTAL THEMES

The first theme, “settler colonialism,” serves to ground this work in an understanding that at the root of these contestations is land. The second theme, “corporate resource extraction,” is centered around the immediate realities of the Dakota Access Pipeline. The third theme, “archaeological knowledge,” focuses on the field of archaeology’s colonial foundations. While the field of archaeology may not be extracting resources, it has may be understood as a means of extracting data. And lastly, “Indigenous ways of knowing” presents alternatives forms of research that prioritize relationships that are reciprocal, responsible, and sustainable.

These themes are highlighted in dialogue as I speak with primarily Indigenous scholars to help me to better understand settler colonialism, desire-based research, Indigenous archaeology, and decolonization.