Greetings from the [un]Holy Land: A Postcard Project from Israel/Palestine

ברכות מארץ ה [לא] קדושה احلاً من ارض ال [غير] مقدسة

By Sophie Schor (University of Massachusetts Amherst)

Greetings from the [un]Holy Land, © Sophie Schor 2017.

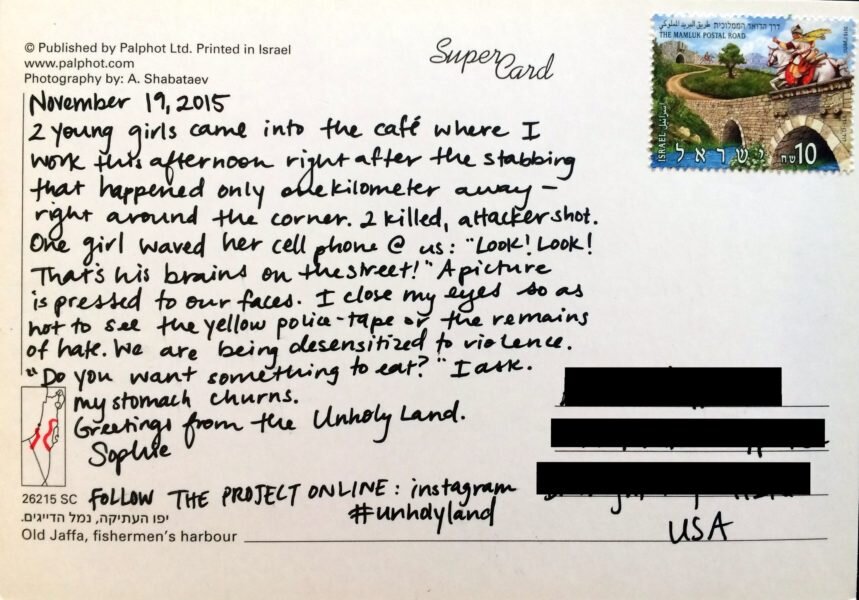

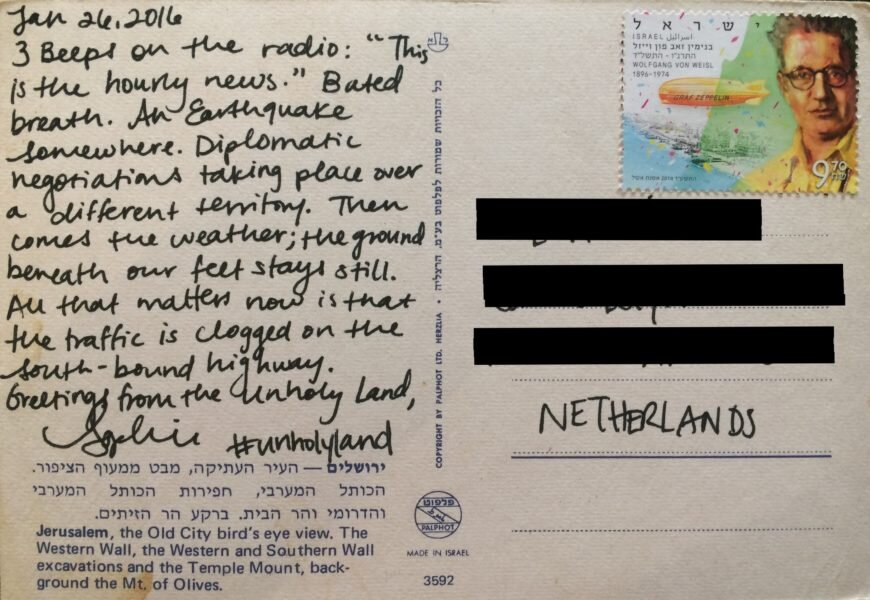

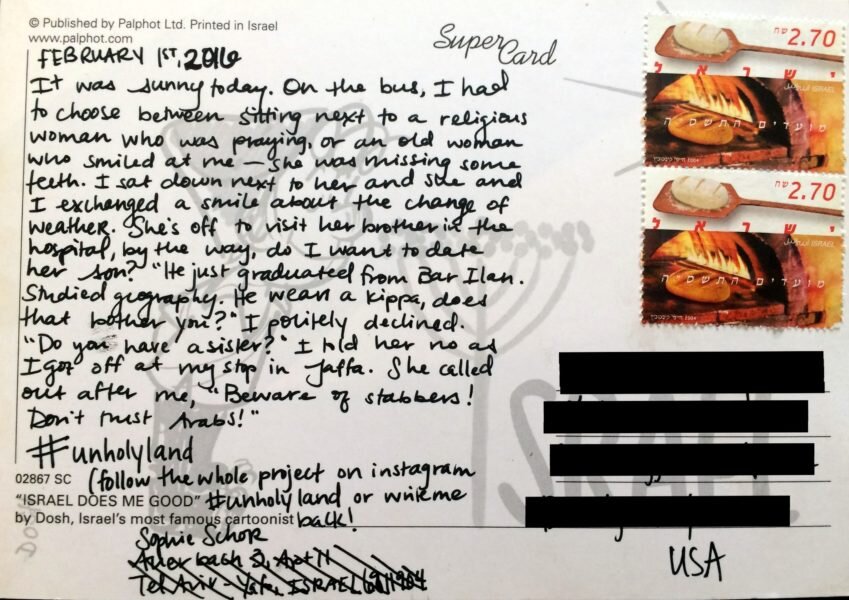

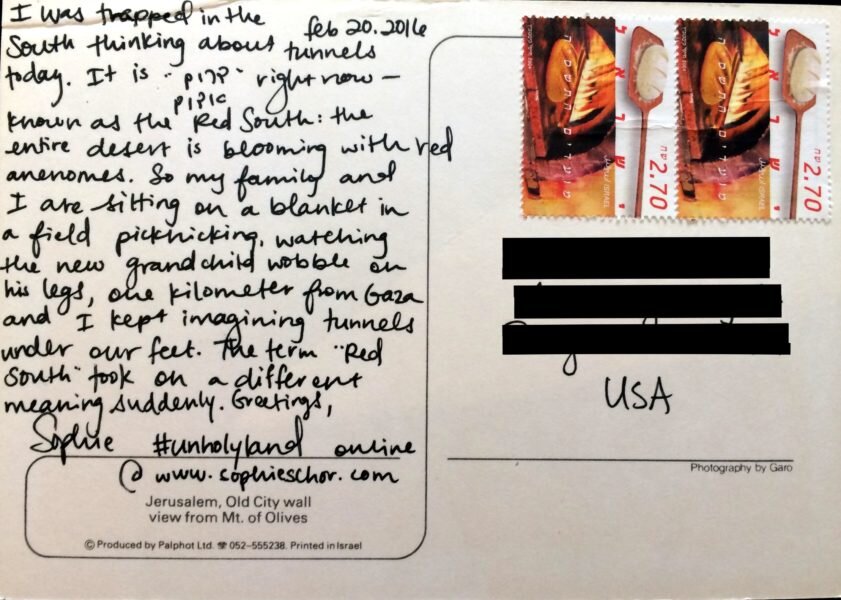

I lived in "the field" in Jerusalem, and Tel Aviv, from 2014-2017. My experiences spanned from the classroom, to family dinners (and debates over who makes the best cucumber and tomato salad), to dedicated nonviolent activism in solidarity with Palestinians and ethnographic research on women-led peace movements. Throughout my time, I struggled to capture the gritty, painful, joyous, and surreal moments of everyday life in Israel and in Palestine. I found that updates on social media lacked the capacity to reveal the contradictions that I faced daily. It was with this in mind, this need to share my stories, that I turned to a different form of communication: postcards.

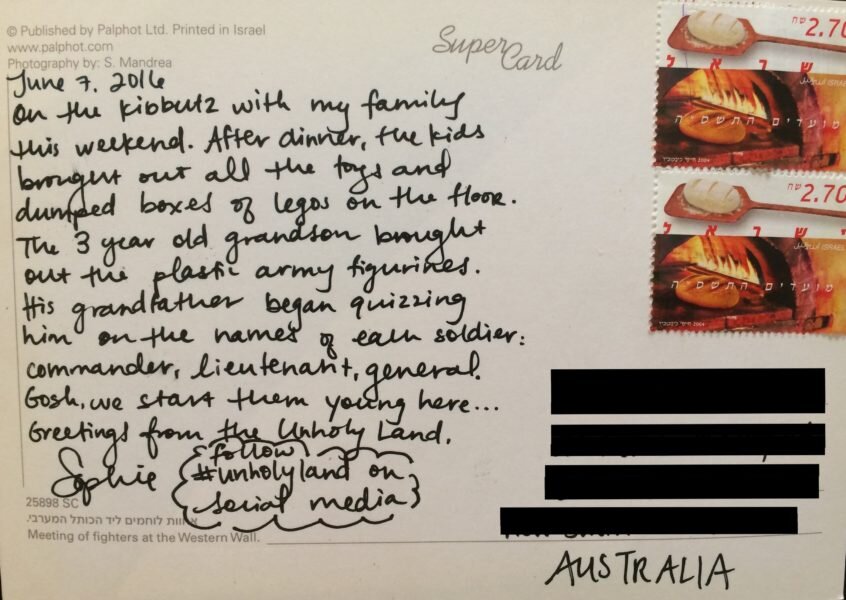

Postcards offered me something that modern communication technologies could not; they were a blend of fieldnotes, journaling, and ethnographic analysis rolled into one. They became a space where I was able to process and reflect, and yet were a step removed from the emotional labor of fieldwork. While my journaling had previously taken form on social media, the events of everyday life in a conflict zone necessitated yet another genre of writing, one that brought my experiences into a tangible realm and contained a meta-layer. The postcards, by fact of being an ethnographic artifact, opened up a conversation between images and my annotations; they were a multivalent fieldnote.

Through daily postcard snapshots (that endure for longer than a Snapchat), I hoped to capture and share the strange intricacies and surreal tensions of daily life and violence in Israel and Palestine. Thus, the postcard project emerged from my experiences and began as a quest for storytelling: How could I share the fraught realities of Israel and Palestine with a larger audience in a more layered and nuanced way than what makes the news? How could I share with the world the conflicting realities in a way that was real? How could I transform these ephemeral and absurd moments into something concrete, something that could be processed and held?

Though I was born in the United States, my mother's entire family lives in Israel. I was registered as a dual citizen by the time I was six months old, and we embarked on our first trip to visit the great-grandparents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, and family friends. From my childhood experiences, Israel was a place of never-ending summer, ice cream, and cousins—not a place of contested territory and intractable conflict. Only when I went to college did I discover that the State of Israel was founded in 1948. My family hadn't lied to keep this fact from me, but they did neglect to mention it, a lie of omission perhaps. Since that discovery, I have studied about Israel and Palestine and in Israel/Palestine on various occasions. I spent time in Jerusalem and Be'er Sheva learning Hebrew in 2011 and 2014. I then moved to Jerusalem in June 2014 with the intention of both studying and integrating into Israeli society and my family; I enrolled at Hebrew University in Jerusalem to pursue a master's degree in Middle Eastern and Islamic studies—as my aunt asked, why would you study the Middle East not in the Middle East?[1]

While living in Israel, I got to know my family. They represent a wide spectrum of Israeli society; some cousins live in a communal Jewish village in the north, surrounded by the Muslim call to prayer echoing off the neighboring hills and Arab villages. Others live in a Kibbutz in the Negev desert in the south, true pioneers of the Secular Labor Zionist project. My aunt, meanwhile, lives in Jerusalem and is a part of the Ultra-Orthodox Haredi community that rejects the State of Israel, claiming that it is not "Jewish" enough. My grandmother lived in the north where, while floating in the Kibbutz pool, you can see the confluence of the Syrian, Lebanese, and Israeli borders collide. There is a total of nineteen cousins in my generation alone: some are religious with up to nine kids, some are finishing their army service, some are studying, some are working. My own family is replete with ideological contradictions.

It was exhilarating to be welcomed into my "tribe." Yet, only two weeks after I moved to Jerusalem, the most recent war with Gaza, Operation Protective Edge, began. My favorite twenty-year-old cousin was called with his company to serve inside the Gaza Strip as a part of the operation. Rockets were flying into Israel and thousands were dying in Gaza. The cycle of violence, hate, superficial politics, and competing nationalisms impacted me on a profound level; I suddenly wanted nothing to do with the State of Israel and its state-sanctioned violence. That rupture shaped my perspective for the next three years, and I became active in communities of peace activists and anti-occupation movements with Israelis and Palestinians.

While engaging in solidarity actions in Palestine, I witnessed the underbelly of occupation. I felt the air constrict in my lungs as we crossed under the shadow of a checkpoint and emerged back in the sun, only to have the sun then blocked by the concrete grey of the Separation Wall. I cringed when I saw signs on the highway and the Arabic name of the location was blacked out by spray paint. I was the only ajnabiyya (foreigner) dancing at an Arab wedding of my friends and clapped until my hands were bright red. I debated with Palestinian friends about the nuances of different politicians, listened to their complaints and frustrations regarding corruption, and sighed wistfully as together we imagined a future different from what we knew. I accompanied Palestinian shepherds with their herds to witness any impediments to their access to their own lands. I harvested olives for families who were unable to touch the soil or the trees that their great-grandparents had planted because they had the "wrong" permit. I joined a coalition and we built, and rebuilt, the Sumud Freedom Camp[2] protest encampment with Palestinians in an act to reclaim private Palestinian land and return a family to their ancestral home. Together, we established a community center for nonviolent organizing in the South Hebron Hills that is still thriving today, three years later, under the leadership of Palestinian youth from the region.[3] As an American Jew and an Israeli against the occupation, I belonged both everywhere and nowhere. After three years, I was overwhelmed by questions and left to pursue a PhD back in the United States.

Israel, Palestine, and the idea of the Holy Land have occupied the imaginations of many people in the world throughout time (see Bar-Yosef 2005; Long 2003; Moors and Machlin 1987; Obenzinger 1999). Whether seen as the home of the three Abrahamic religions or as a political flashpoint calling potential partisans to join one righteous side or the other, Israel's "imaginative geographies" captivate the world (Larsen 2006; Said 1975). I wanted to use my experiences to shatter the stereotypes and illusions surrounding this space, and I found that postcards offered me the freedom to write my own narrative on the back—one that could explicitly contradict the images, or the established narrative, on the front.

The project involved selecting twenty journal entries from years of daily journaling (one could even say from my "fieldnotes"). I then narrowed down the entries that contained striking events or text that correlated to an image on an appropriately contradictory postcard. I mailed the collection on my final day in Israel before moving back to America. I sent them to friends, colleagues, and solicited addresses of friends of friends around the world. My Lebanese friend requested that I send it to a PO box of a friend in the United States so that she could forward it to him (could an Israeli stamp make it past the Lebanese-Israeli border? Would he be blacklisted for having contact with an Israeli? He did not want to find out).

I became postcard-obsessed. I would walk into any store that I saw selling postcards and comb the displays. I was interested in the visual images selected to represent Israel and Palestine and the "tourist gaze" those images distilled (Waitt and Head 2002, 324). What kind of national self-narratives were being propagated by images meant to be sent elsewhere? How does the State of Israel seek to represent itself to tourists and to outsiders? What images were quintessential, and how did they fit or conflict with what I had experienced during quotidian life? What images were absent? What stories were being erased? How do the images on the front relate to the text on the back? Dissonance can be enlightening.

The menial and sustaining activities of walking to work, taking the bus, and grocery shopping all became sites of investigation. I wrote daily. And I hunted for the postcard image to match the subject I discussed. I searched for a postcard of red poppies for four months to line up with my reflections from visiting my family in the Negev during the "Red South," a seasonal occurrence when red blossoms cover the entire south and families picnic and couples take selfies. I eventually found it in a tiny shop with ancient books on a street in Tel Aviv when I was lost one day.

My favorite postcards quickly became the ones that echoed my project by offering, "Greetings from the Holy Land!" Naming is an act of power and often a clear demarcation of what "side" you are on.[4] I attempted to evade this political declaration by picking "Holy Land" as an entry point to engage with the place—"Holy Land" is used in an almost "neutral" way to refer the land between the river and the sea because it alludes to the overlapping sacred geographies of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam without privileging any one religion's claims over another. And yet, holiness connotes goodness and justice, things that are both present and strikingly absent in Israel and in Palestine. I wondered what makes something unholy. How does the construction of Israel as a holy place interact with the profane, with the mundane, and even with the unholy events of daily life—especially in Israel's role in occupied Palestine? The project therefore also provokes a reflection on holiness and invokes a participatory subjectivity of both the author (me) and the reader (the addressee).

Postcards are often used to reinforce the dominant image of a place, and through the stories they tell they can reify the structures of power that maintain stereotypes (Fraser 1980); they can exoticize the real (see Alloula 1986; Burns 2004). It is with this in mind that I began my search. What image could best represent Tel Aviv? Jerusalem? Jaffa? Ramallah? Nablus? What sites appeared over and over again to symbolize the country(ies)? What languages were used to label the image? Were there maps? Did those maps include internationally recognized borders? How often did idealized images of soldiers and sexualized women appear? Of beaches? Of the Dome of the Rock? Of the Wailing Wall? Of the Separation Wall? Of Banksy's graffiti on the Separation Wall? I challenged the hegemonic images by doctoring the postcards—both the front and the back—to reflect the story I was trying to tell. "Greetings from the Holy Land" became the "[un]Holy"; tiny inset maps gained new borders from my red pen that show the (erased) demarcated territories and 1948 borders.

The cardboard back of the postcards became one medium to tell these stories, but stamps also played a role. I remember purchasing stamps to send to the United States (which differed from the stamps to Europe), and I was given a stamp that advertised Taglit (Birthright). Birthright is a free ten-day trip for young American Jews to visit Israel, all expenses paid. The trip is highly politicized and critiqued for being a propaganda machine.[5] I was suddenly stuck with a stamp that I had to carefully designate its recipient. I eventually picked a friend, and academic, whose work focuses on the tourism and impact of educational trips that encounter "the Other" for young Jews. I knew she would appreciate the adhesive irony.

While the internet is public, a postcard is public in a different way; while it is designated for a particular recipient, anyone can read what is written on the back. It is therefore "semi-public" (Östman 2004). The project thus interrogated routes of communication by shifting from a virtual space to a concrete object that will pass from me to its addressee and be held in the hands of many others along the way. Who knows who will come across my message? How will the Israeli postal worker react to my message that reads:

What happens if (when) others read the postcard? What if the recipient wants to respond? Will this interaction with a printed object prompt them to think about their own life and the world around them? Will the postcard ever arrive to its intended destination? Is mail still a viable mode of communication in the twenty-first century?[6] Will my generation be the last to remember buying stamps?

Aware of these challenges, I curated a virtual gallery to accompany the transient cards; I photographed them all—this was the only time the entire set would be in conversation with each other as objects—and posted them online through multiple channels: Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and my personal website.[7] I included a hashtag, #unholyland, as a concession to the preeminence of cyber conversations. Then I sent them off to be permanently scattered.

As Adjin-Tettey et al. (2008) write, my postcards were "a one-sided missive with no return address . . . [one] can only speculate about how and if our postcard was received." While I asked for photos of the postcards once they arrived—water wear, tears, markings, dirt and all—there was still a lopsided balance to the communication. The content did not elicit a normal correspondence and conversation. In a way, I was using my friends as a space for external venting, as a receiver of my written screams of fear, frustration, anger, and joy. Furthermore, the form of the postcard did not leave open a duality to the project: I no longer lived there, so where would someone send a postcard (back) to? The conversation therefore took place between me and the journey of the card in time and space. But the materiality of the objects helped to solidify the experiences that I had witnessed. Especially in a conflict zone where every detail is debated, the tangible quality of the postcards affirmed that what I experienced was equally "real."

The final postcard I sent was to my parents before embarking on a plane to move back to my hometown to begin my PhD, after many years away. It was the only postcard I had been able to find that had both Hebrew and Arabic on it. I wrote,

At the end of the day, I still believe that there is an underlying heartbeat of justice to this world; that human life is worth something and that each person deserves to be treated with dignity, nurtured to grow, and have the opportunity to thrive. That heartbeat, that constant pulse, brushes away the fear that 50 years of occupation will pass, and no one will bat an eye. It gives me hope that systems of oppression will be toppled, and it reminds me that human beings are both more creative and capable to change than I give us credit for. It tells me that through our actions, we make the mundane meaningful, the profane sacred, and the unholy holy.

The postcards helped me to process the trauma of violence that is the backbone of conducting research in a conflict zone (Wood 2006). It provided me an outlet to communicate with my friends, my family, and my global community. It helped to bridge those awkward "How was living in Israel?" conversations—where does one even begin? The multilayered approach of the postcards opened up conversations that were colorful and authentic. It also prompted me to reflect critically on images and the power of representation in conflict zones. In a space that is in a perpetual state of existential and violent crises, everything can be politicized—even something as inconspicuous as a postcard back home.

For the full project (text and images), see www.sophieschor.com

REFERENCES CITED

Adjin-Tettey, Elizabeth, Gillian Calder, Angela Cameron, Maneesha Deckha, Rebecca Johnson, Hester Lessard, Maureen Maloney, and Margot Young, 2008. "Postcard from the Edge (of Empire)." Social & Legal Studies 17 (1): 5-38. doi:10.1177/0964663907086454.

Alloula, Malek. 1986. The Colonial Harem. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Bar-Yosef, Eitan. 2005. The Holy Land in English Culture 1799-1917: Palestine and the Question of Orientalism. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Burns, Peter M. 2004. "Six Postcards from Arabia: A Visual Discourse of Colonial Travels in the Orient." Tourist Studies 4 (3): 255-75.

Fraser, John. 1980. "Propaganda on the Picture Postcard." Oxford Art Journal 3 (2): 39-48.

Larsen, Jonas. 2006. "Geographies of Tourist Photography." In Geographies of Communication: The Spatial Turn in Media Studies, edited by Jesper Falkheimer and André Jansson, 241-57. Gothenburg: Nordicom.

Long, Burke O.. 2003. Imagining the Holy Land: Maps, Models, and Fantasy Travels. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Moors, Annelies, and Steven Machlin. 1987. "Postcards of Palestine: Interpreting Images." Critique of Anthropology 7 (2): 61-77. doi:10.1177/0308275X8700700206.

Obenzinger, Hilton. 1999. American Palestine: Melville, Twain, and the Holy Land Mania. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Östman, Jan-Ola. 2006. "The Postcard as Media." Text & Talk—Interdisciplinary Journal for the Study of Discourse 24 (3): 423-42. doi:10.1515/text.2004.017.

Said, Edward. 1978. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books.

Waitt, Gordon, and Lesley Head. 2002. "Postcards and Frontier Mythologies: Sustaining Views of the Kimberley as Timeless." Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 20 (3): 319-44. doi: 10.1068/d269t.

Wood, Elisabeth J. 2006. "The Ethical Challenges of Field Research in Conflict Zones." Qualitative Sociology 29:373. doi:10.1007/s11133-006-9027-8.

NOTES

[1] A question that has rolled in my mind ever since—is Israel the Middle East? Who denotes what is and is not the Middle East? This is further complicated by the disciplinary divides in Israeli academia (and elsewhere) that separates Israel studies from Middle Eastern studies, and by Israel's own self-perception as being a "villa in the jungle" as previous prime minister Ehud Barak proclaimed. For further discussions on this see: Podeh, Elie. 2006. "Israel in the Middle East or Israel and the Middle East: A Reappraisal," in Arab-Jewish Relations: From Conflict to Resolution?, edited by Elie Podeh and Asher Kaufman, 93-113. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press., and Podeh, Elie. 1997. "Israel in the Middle East: A Reconsideration of Its Regional Status," Medina, Mimshal Vihasim Benleumiyim, Vol. 41-42, 280-95. [Hebrew].

[2] Schor, Sophie. 2017. "40 days and 40 nights." +927mag, https://972mag.com/40- days-and-40-nights-building-a-new-reality-in-sumud-freedom-camp/128500/, and Sumud Freedom Camp.

[3] Youth of Sumud. 2019. https://www.facebook.com/youthofsumud1/.

[4] What do we call Israel: Palestine? The Land of Israel (Eretz Yisrael)? ‘48? Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territories? Judea and Samaria? The national home of the Jewish People? Palestina?

[5] See Farah Stockman. 2019. "Birthright Trips, a Rite of Passage for Many Jews, Are Now a Target for Protests." NYTimes. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/11/us/israel-birthright-jews-protests.html, and https://www.notjustafreetrip.com.

[6] See Lepcha in this series.

![Greetings from the [un]Holy Land, © Sophie Schor 2017.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f8b0aff4e842e4e3eece641/1629250414223-L4QM7NYJA0HVQHY533M9/Schor-Figure-1.jpg)

![Postcard from Jaffa, Greetings from the [un]Holy Land, © Sophie Schor 2017.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f8b0aff4e842e4e3eece641/1629250735722-IU5NHYRJOLROKST55OT7/Schor-Figure-2-856x600.jpg)

![Postcard from Jerusalem (Al-Quds), Greetings from the [un]Holy Land,© Sophie Schor 2017.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f8b0aff4e842e4e3eece641/1629250828834-Q9VS0ZH1XW9SLQLP4GQW/Schor-Figure-4-899x600.jpg)

![“Sunny Stabbings,” Greetings from the [un]Holy Land,© Sophie Schor 2017.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f8b0aff4e842e4e3eece641/1629250897909-C7VWM8B6NPXP66CP4TR7/Schor-Figure-7-840x600.jpg)

![Postcard from the Red South (D'rom Adom), Greetings from the [un]Holy Land,© Sophie Schor 2017.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f8b0aff4e842e4e3eece641/1629250941500-CDLQ7JVMASTNE2RU2Q67/Schor-Figure-9-844x600.jpg)

![Postcard from Militarized Jerusalem, Greetings from the [un]Holy Land,© Sophie Schor 2017.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f8b0aff4e842e4e3eece641/1629250992301-ZIO1P89EXP5XHKSPSTTO/Schor-Figure-11-866x600.jpg)

![Postcards with Edits, Greetings from the [un]Holy Land,© Sophie Schor 2017.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f8b0aff4e842e4e3eece641/1629251024994-PTH3HIFS63WCURAMJ8GE/Schor-Figure-6-1-858x600.jpg)

![Taglit (Birthright) Stamp, Greetings from the [un]Holy Land,© Sophie Schor 2017.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f8b0aff4e842e4e3eece641/1629251092835-OXOZV9HLRJMTN0BZCGRW/Schor-Figure-13-852x600.jpg)

![“Damascus Gate Stabbing Season's Greetings,” Greetings from the [un]Holy Land,© Sophie Schor 2017.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f8b0aff4e842e4e3eece641/1629251135722-2TANL7VXBM89UOR4T15X/Schor-Figure-15-870x600.jpg)

![“The Final Card,” Greetings from the [un]Holy Land, © Sophie Schor 2017.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f8b0aff4e842e4e3eece641/1629251185148-GD7T108FWF9WHY8Q199C/Schor-Figure-18-867x600.jpg)